My Article published in the Newsanalytics Journal Mar 25.

Greenland is the world’s largest island, located in the Arctic, to the northeast of Canada. Politically, it is an autonomous territory of Denmark, though it has its own government and parliament. With a landmass of approximately 2.16 million square kilometers, Greenland is sparsely populated, with a population of around 56,000 people, most of whom live along the island’s coast. The majority of Greenland’s land is covered by an ice sheet, which holds a significant portion of the world’s freshwater. This ice sheet is vital to global climate patterns, as its melting could raise sea levels and disrupt ocean currents. While Greenland is rich in natural resources such as minerals, oil, and gas, its remote location and harsh environment make resource extraction challenging. Due to its strategic location, it has historically been important to both European and American interests, particularly during the Cold War, when the U.S. established military bases there.

Recent Limelight. Greenland has recently been at the center of international attention due to renewed interest from the United States in acquiring the territory. In December 2024, President Donald Trump reiterated his proposal for the U.S. to purchase Greenland from Denmark, citing national security concerns. This proposal builds upon a similar offer made during his first term, which was declined by the Danish government. In response to these developments, 85% of Greenlanders oppose the idea of becoming part of the United States. Greenland’s Prime Minister, Múte Egede, has emphasised that while Greenland is open to discussions about common interests with the U.S., the island is not for sale. The situation has led to increased diplomatic activity, with Denmark announcing plans to invest 14.6 billion crowns ($2.04 billion) to bolster its military presence in the Arctic. European leaders have also expressed support for Denmark, highlighting Greenland’s strategic importance in global geopolitics. These events underscore Greenland’s significant role in international affairs, particularly concerning Arctic sovereignty, natural resources, and global security dynamics.

Greenland’s Resource Potential. Greenland has vast natural resources, including rare earth elements, uranium, oil, and gas. These resources are essential for global industries, including defence, technology, and renewable energy. While Greenland’s government has moved away from oil exploration, its untapped reserves remain a strategic interest for global energy markets. Greenland’s waters are among the richest fishing grounds, a key economic driver and a point of interest for international players. As climate change makes resource extraction more feasible, Greenland faces a dilemma between economic development and environmental protection. Foreign mining and energy investment must balance economic benefits with sustainability concerns and geopolitical risks.

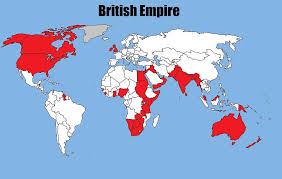

Strategic Location: Trade Routes. Greenland’s location in the North Atlantic and Arctic regions makes it an invaluable strategic asset. It lies between North America and Europe, serving as a crucial link for military and trade operations. The island provides access to key shipping lanes, including the emerging Arctic sea routes, which are becoming more navigable. As Arctic ice melts, new shipping lanes such as the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route are opening up, reducing travel distances between Asia, Europe, and North America. Control over Greenland enhances the ability to monitor and regulate these routes, making it a strategic chokepoint in global trade.

Strategic Location: Militarily: Additionally, Greenland’s airspace and maritime routes are crucial for transatlantic military logistics. In any potential conflict in the North Atlantic, control over Greenland would be pivotal for ensuring dominance in the region. Greenland provides a staging ground for air and naval operations in both the Atlantic and Arctic, making it essential for NATO’s security umbrella. The U.S. maintains Thule Air Base in northern Greenland, a key component of the North American early-warning defence system. Thule is home to a ballistic missile early warning radar and a deep-space surveillance system.

Superpower Rivalries in Greenland

The Arctic as a New Global Arena. Greenland, the world’s largest island, has become an increasingly significant player in global geopolitics. Its strategic position in the Arctic, vast natural resources, and the effects of climate change have heightened interest from global superpowers such as the United States, Russia, and China. As geopolitical tensions rise, Greenland’s role in security, trade, and military strategy continues to expand, making it a focal point of international competition.

U.S. Interests and Military Presence. The United States has long viewed Greenland as an essential part of its Arctic strategy and has maintained a strategic presence in Greenland for decades. During World War II, the U.S. took over defence responsibilities for Greenland from Denmark to prevent German occupation. Since then, it has remained a key ally in Arctic security. In 2019, former U.S. President Donald Trump proposed purchasing Greenland from Denmark, highlighting its strategic importance. Though Denmark and Greenland rejected the proposal, it underscored the island’s increasing geopolitical value. The U.S. has continued to strengthen ties with Greenland through economic aid and security cooperation, recognising its role in countering Russian and Chinese influence in the Arctic.

Russian Expansion in the Arctic. Moscow views the Arctic as crucial for national security, energy extraction, and global influence. Russia has been actively expanding its Arctic military capabilities, reopening Soviet-era bases, deploying new icebreaker ships, and establishing Arctic brigades. The country considers the Arctic a key strategic frontier for national security and resource exploitation. Russia’s growing military infrastructure, including reported hypersonic missile deployments and submarine operations, has heightened concerns among NATO allies.

China’s Economic and Strategic Interests. China identifies itself as a “near-Arctic state” and has actively sought economic opportunities in Greenland, investing heavily in Arctic infrastructure, scientific research, and resource extraction. Greenland’s rare earth minerals are mainly of interest to China, which seeks to diversify its supply chains. China has also pursued scientific research in the Arctic, positioning itself as a key player in Arctic governance. However, its increasing presence has alarmed Western powers, who view Beijing’s activities as part of a broader strategy to expand its geopolitical influence. In 2018, the United States successfully pressured Denmark to block Chinese investments in Greenland’s airport infrastructure, fearing potential military implications. In 2021, Greenland’s newly elected government banned uranium mining, blocking a major Chinese-backed project. This decision was seen as a move to limit Chinese influence in the region and align more closely with Western allies.

Greenland’s Political Landscape and Future Prospects. Greenland is an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, with its own government and growing aspirations for independence. While it relies on Denmark for defence and financial support, Greenland has sought greater economic and political autonomy. For Greenland, balancing economic development with national security concerns remains a challenge. Denmark has recognised Greenland’s strategic importance and has increased its Arctic military budget. In 2024, Denmark announced a $2 billion investment to enhance its Arctic security capabilities, reinforcing its commitment to maintaining stability in the region. The U.S. has shown interest in strengthening ties with Greenland outside of Danish influence and its role in NATO could grow, given its strategic military importance. The island’s leadership must navigate pressures from global powers while ensuring sustainable growth and environmental protection.

Conclusion. Greenland is not just a remote ice-covered island, it is a critical player in global security dynamics. Its location, resources, and military significance make it a key area of interest for major powers, including the United States, Russia, and China. As Arctic geopolitics intensify, Greenland’s strategic importance will only increase. Whether through military cooperation, resource management, or diplomatic engagements, Greenland will remain at the heart of global power dynamics in the 21st century. Ensuring its stability and security will be crucial for maintaining Arctic balance and broader global stability.

Please Do Comment.

For regular updates, please register your email here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

References:-

- Bader, Julia, and C. D. E. O’Neil. Arctic Geopolitics: Security, Resources, and the Shifting Balance of Power in the Arctic. New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Smith, M. L. R. The Arctic and World Order: Climate Change, Security and the Future of the Global Commons. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Friedrich, Daniel, and Stefan Sommer. “Greenland’s Strategic Importance: A New Cold War?” Journal of International Security Studies 28, no. 3 (2022): 45-67.

- Young, Oran R. “The Geopolitics of Greenland: Great Power Rivalry in the Arctic.” International Journal of Arctic Studies 13, no. 2 (2019): 103-123.

- McGovern, Mike. “Climate Change and the Arctic: Security Risks and Strategic Opportunities.” Security Studies Review 12, no. 4 (2021): 78-94.

- Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies. Greenland: A Military Asset for the West? Oslo: Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies, 2023.

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The Arctic as a Strategic Frontier: Greenland’s Role in U.S. Defense and Foreign Policy. Washington, D.C.: CSIS, 2020.

- RAND Corporation. The Geopolitical Implications of Arctic Resource Extraction and Military Infrastructure in Greenland. Santa Monica: RAND, 2021.

- The Guardian. “Greenland’s Changing Role in Global Geopolitics.” The Guardian, July 14, 2023.

- BBC News. “Greenland’s Military Significance in the Arctic: A New Era.” BBC News, March 5, 2022.

- Foreign Policy. “Greenland’s Geostrategic Location: The Next Global Flashpoint?” Foreign Policy, August 3, 2021.

- The Arctic Institute. “Greenland’s Military Infrastructure and U.S. Strategic Interests in the Arctic.” The Arctic Institute, August 2022.

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.