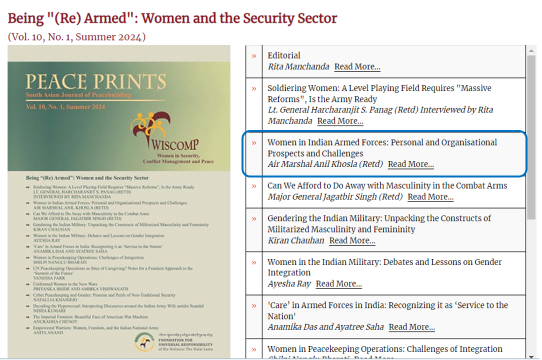

My Article Published in the journal Peace Prints

South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding

(Vol. 10, No. 1, Summer 2024)

Pic Courtesy: Internet

“Not all women wear pearls and shoes to work; some wear dog tags and combat boots.”

-Author Unknown

Women’s participation in the armed forces has evolved significantly over the years worldwide, with a growing recognition of their valuable contributions to the defence and security of the country. Many countries now allow women to serve in the armed forces in numerous roles. The extent of participation and roles vary from country to country, depending on cultural norms, legal frameworks, and military policies.

Traditionally, the Indian armed forces have also been predominantly male-dominated; however, the inclusion of women was inevitable with changes in societal norms and perceptions. The roles and opportunities for women have expanded over the years, with women now serving as pilots, engineers, and administrators, among others. Associating changes in military policies preceding or succeeding these decisions.

The history of women in the Indian defence services is a story of gradual progress and increasing participation from support services and roles to combat and command roles. The Indian Air Force, for instance, has implemented various initiatives to promote gender equality and equal opportunities for women. These include recruitment drives, training programs, and policy changes. IAF has been relatively more progressive than the three services in gender mainstreaming, with significant strides made in recent years towards achieving gender equality and providing equal opportunities for women in the workforce.

While including women in the armed forces brings several benefits, specific challenges and barriers still exist. These include aspects related to cultural and societal norms, such as traditional gender roles and expectations, which can hinder women’s acceptance and integration into the armed forces. Career opportunities and progression, physical and psychological suitability for combat roles and leadership positions, gender integration, gender equality, gender bias, and gender discrimination are some of the critical challenges. The Indian Air Force, like other branches, has been working to address these issues, but there is still work to be done. Harassment prevention, redressal mechanisms, judicial recourse, physical and mental fitness norms, etc., need to be reviewed periodically for mid-course corrections.

Evolutionary Approach. Historically, women were largely excluded from combat roles in defence forces. They were primarily involved in support roles, such as nursing, administrative work, and other non-combat positions. Women’s roles were often undervalued and underestimated in these contexts. World War I and II marked a turning point for women’s involvement in defence services. The demand for manpower led to expanding women’s roles beyond traditional boundaries. Women took up roles as mechanics, drivers, communications operators, and more, both in combat zones and at home. Over time, many countries officially integrated women into their defence forces. This integration initially focused on non-combat roles but gradually expanded to combat positions. The 21st century has witnessed a shift in attitudes toward women’s roles in defence services. Many nations have recognised the value of diversity and the skills women can bring to various military roles. Efforts have been made to remove barriers to entry and promotion for women within the military.

Scan – Militaries of the World. Women’s participation in defence services worldwide has evolved significantly over the years, and several countries have made considerable strides in integrating women into their defence forces. The extent of participation and roles allowed for women varies from country to country. According to Wikipedia, non-conscription countries, particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have the highest levels of female military presence. Besides these, Israel, Australia, and several European and Nordic nations have attained a high level of integration. There is a growing recognition of women’s valuable contributions to the defence and security of these countries. The United States, in particular, has played a pioneering role in inducting women into the armed forces. Israel is known for its high representation of women in the armed forces. The Israel Defence Forces (IDF) is among the only armies in the world that conscript women into its ranks under a mandatory military draft law. Countries like Eritrea and Israel have the largest share (about 33 per cent) of women in the armed forces. RAF has the highest proportion of females in the UK Regular Forces. The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) was one of the first military forces to allow women to serve in all occupations. Canada is a world leader in the number of women in its military and the areas where they can serve.

Women in the Indian Defence Services

Historical Evolution. The inclusion of women in the Indian Armed Forces started during British rule in 1888 with the formation of the Indian Military Nursing Service (MNS). After India’s independence, military nurses were granted regular commissions as per the Army Act of 1950. In 1954, the all-women’s MNS corps was brought under the Army Rules along with the Army Medical Corps and Army Dental Corps, constituting the Armed Forces Medical Services (AFMS). The role of women in the armed forces was limited for a long time to a medical capacity, i.e. as doctors and nurses. In 1992, the Army, Air Force, and Navy began inducting women as Short Service Commission (SSC) officers under the Women Special Entry Scheme. This was the first time women were allowed to join the military outside the medical field, and women’s entry was seen as regular officers in aviation, logistics, law, engineering, and executive cadres. Initially, women officers could serve for five years, and their service could be extended by another five years. In 2006, the policy was modified to allow women to serve for 14 years as SSC officers. In 2008, the permanent commission was granted to women in Judge Advocate General and Army Education Corps departments. Through the years, women have been inducted into various arms and branches of the armed forces. Women were not allowed to serve in front-line combat roles until 2015 when the government approved a plan to induct women into the fighter stream of the Air Force. This opened combat roles for women as fighter pilots. The Navy also has women as pilots and observers on its maritime reconnaissance aircraft, a combat role. In 2019, the permanent commission was extended to women in eight departments in the Indian Army – Signals, Engineers, Army Aviation, Army Air Defence, Electronics and Mechanical Engineers, Army Service Corps, Army Ordinance Corps, and Intelligence.

Women in Armed Forces in India. Indian security is looked after by the armed forces, which consist of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and supported by the Indian Coast Guard and the paramilitary services/forces (BSF). Women have been part of these forces and made significant strides, increasing their participation. The MoS for Defence recently shared information in the Lok Sabha about the number of women serving in the Armed forces. According to the information shared, the strength of women officers in three services is eleven thousand four hundred fourteen. The total number includes officers, other ranks, and those in medical, dental, and nursing services. The number of women personnel employed in the three services, excluding those in medical, dental, and nursing, comes to 4,948. The exact numbers in each service vary; however, the Army has the maximum numbers numerically. Reports in the open domain suggest that percentage-wise, the women’s strength in the Army is approximately 3.8% compared to 13% of the Air Force and 6% of the Navy. Recently, the Indian government has taken significant steps to increase the percentage ratio of women (officers and other ranks) and towards their empowerment. The Indian Armed Forces is seeing a surge in the participation of women. Women have started enlisting in the military under the Agnipath program as well. The policies and rules regarding their career progression, employment, and promotional aspects are becoming gender-neutral to provide them equal opportunities. All branches of the Indian Armed Forces now have women in combat roles and are allowed command appointments on par with males. To ensure greater inclusiveness, gender parity, and participation of women in the forces, women are being inducted into Sainik schools and defence academies. Sainik schools were mandated to prepare future armed force officers and were open only for boys. From 2018 onwards, they have been open to girls as well. Women’s entry started in the National Defence Academy from July 2022 onwards. Participation in individual service is as follows:-

Indian Air Force. The Indian Air Force has been at the forefront of gender integration, with women being inducted into the force since 1992. According to inputs from retired Air Chief Marshal NC Suri, the first induction of women officers was in 1992. At that time, there were thousands of applicants for 12 vacancies in the administrative branch. As the first induction, the selected candidates performed exceptionally well. In IAF, Women serve in various roles, including flying (fighter jets, transport aircraft, and helicopters), and also hold influential positions in other ground duty branches like administration, logistics, air traffic control, navigation, engineering, meteorology, accounts, judge advocate general, and logistics along with their male counterparts. The IAF employs the most significant percentage of women officers among the three armed forces. According to the Press Information Bureau, as of March 01, 2023, the strength of women officers in the IAF (excluding Medical and Dental branches) is 1,636. IAF follows a gender-neutral approach to the employment of women. They are considered at par with their male counterparts, with no differentiation in type and quantum of work. The rules provide equal opportunities, even empowering them to hold key appointments, including that of Commanding Officers in Combat Units of various field units. For the first time in the IAF’s history, a woman officer has commanded a frontline combat unit (missile squadron), shattering the proverbial glass ceiling. Indian Air Force started employing women as transport and helicopter pilots in 1994. The women officers proved their mettle and performed well in these roles (including missions related to disaster management). They were found to be at par in performance with their male counterparts. Modern air combat in the digital age involves the management of aircraft systems and weapons. In present-day air combat with beyond-visual-range missiles, one may not even see the enemy in the air. Fighter flying needs a high level of physical and mental fitness. These requirements are gender-neutral. In 2015, a decision was taken to induct women into the fighter stream. In 2016, the first batch of women officers was commissioned in the fighter stream. These women pilots now fly MiG-21s, Sukhoi-30s, MiG-29, and the latest Rafale jets. The experimental scheme to induct women officers into all combat roles, initiated by the IAF in 2015, has now been regularised into a permanent scheme. The IAF remains a favourite among the three services for women because it offers them a thrilling environment, flying opportunities, and the chance to be part of combat operations.

Indian Army. Women have been serving for more than 100 years in the nursing and medical branch of the Army. In 1992 women were inducted under Women’s Special Entry scheme of short service commission for 5 years, in the Army Service Corps, Army Ordnance Corps, Army Education Corps, and Judge Advocate General Department. Later, the entry of women was opened in the Electrical and Mechanical Engineering Corps as well as the Intelligence Corps. In 1996, the SSC of 5 years was extended to 10 years, and in 2004, it was increased to 14 years. Till the year 2018, women were recruited only as officers in the Indian Army. In the year 2019, women were inducted into the military police. In July 2020, women were granted permanent commission in 10 streams {Army Air Defence (AAD), Signals, Engineers, Army Aviation, Electronics and Mechanical Engineers (EME), Army Service Corps (ASC), Army Ordnance Corps (AOC), and Intelligence Corps in addition to the existing streams of Judge and Advocate General (JAG), and Army Educational Corps (AEC)} and Remount and Veterinary Corps (RVC) was added in 2023.

Consequent to the grant of the Permanent Commission, and putting in place a gender-neutral Career Progression policy the Indian Army opened up avenues for Women Officers to serve as pilots in the Corps of Army Aviation. Women officers are being considered for Colonel (Select Grade) ranks and are being given command appointments. Women are being inducted in other ranks in the Corps of Military Police under the Agnipath Scheme.

Indian Navy. The induction of women as officers in the Indian Navy commenced in 1992 as short-service commissioned officers in a few branches. Since then the Indian Navy has gradually opened up all branches to women officers. By 2019 they were being inducted into 11 branches – including observation, legal, logistics, education and flying. At present women comprise six percent of the workforce. A Permanent Commission is being granted to those eligible. Women are also being recruited as sailors for the first time under the Agnipath Scheme. Twenty percent of sailor positions have been reserved for them. Women officers are being deployed on board warships, as Naval Air Operations (NAO) Officers on Helicopters, in Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) stream, on Diplomatic and other Overseas Assignments.

Women in the Paramilitary. In addition to the three main branches of the armed forces, women have been inducted into the paramilitaries: Indian Coast Guard and Assam Rifles and the Central Armed Police Forces.

Indian Coast Guard. Women can join the Indian Coast Guard in officer ranks as general duty, pilot, or law officers. In January 2017, the Indian Coast Guard deployed four women officers of assistant commandant rank on board a hovercraft ship patrolling the Indian maritime zone. Following the Supreme Court’s directive of February 2024, the Indian Coast Guard is to ensure the grant of Permanent Commission to eligible women officers.

Assam Rifles. In April 2016, Assam Rifles inducted the first batch of 100 female soldiers. They are being deployed for Cordon and Search Operations (CASO), Mobile Check Posts (MCP), and road opening operations in various battalions. Increasingly women soldiers are needed for performing tasks such as searching, frisking, and interrogation of women, crowd control, and dispersal of female protesters. In August 2020, an estimated 30 rifle-women from Assam Rifles were deployed along the LoC for the first time.

Central Armed Police Forces. The Central Armed Police Forces consist of five forces, namely the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Border Security Force (BSF), Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB) and Central Industrial Security Force (CISF). Women from the Indian Police Service have been seconded to these forces, and some of them have led these forces as Director Generals. In March 2016, direct entry of women as officers and constables was allowed into these forces. In March 2016, Home Minister Rajnath Singh announced that women would be inducted into constable-rank up to 33 % of the force in CRPF and CISF and up to 15% in the border guarding forces of BSF, SSB, and ITBP. CRPF has six Mahila Battalions. The first Mahila Bn in CRPF, the 88(M) Bn was raised in 1986 and is HQ at Delhi.

Other Forces. Women also serve in the National Security Guard (NSG), Special Protection Group (SPG), Railway Protection Force (RPF), National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) and Border Roads Organisation (BRO). The National Security Guard (NSG) Black Cat Commandos first inducted female commandos in 2011–12. In 2015, the government announced that female NSG Black Cat Commandos, who undergo the same training as their male counterparts will be deployed in counter-terrorism operations as they also are required to perform VIP protection duties. The Special Protection Group (SPG) inducted female commandos in 2013. The Railway Protection Force (RPF) has a female unit, Shakti Squad.. National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) got its first woman commander in 2015. In June 2021, BRO appointed the first woman commanding officer to command a BRO Company as a part of the India-China Border Roads.

Related Aspects: Analysis

“Valour knows no gender.”

– Barack Obama

Benefits of Inclusion. Including women in the armed forces has several military and societal benefits. The inclusion of women broadens the pool of selection. It improves the intake quality and offsets the falling recruitment and retention rates. Including women leads to diverse yet balanced perspectives, enhanced problem-solving, and a more inclusive and representative military force. Overall, a mixed-gender force makes the military strong. Women joining the armed forces has a positive impact on society as a whole by generating tremendous respect for women and their abilities. It helps in breaking down gender stereotyping and promotes gender equality. Women who have served in the services have a high degree of self-confidence. They become self-reliant and are better equipped to cope with or face difficult situations in life.

Performance. Women’s performance in defence services is at par with their male counterparts. Women have demonstrated their capabilities and dedication in various roles, including combat situations. Studies and observations from countries that have integrated women into combat roles suggest that their performance is generally consistent with the standards set for those roles. Many women have achieved high ranks and distinctions within defence services, proving their competence and dedication. In the services, one comes across many women officers who perform exceptionally in their jobs and are of the utmost commitment, sometimes even at the cost of personal life. However, others have lower motivation levels or have other priorities in life. Another observation is that the initial women inductees’ performance level was generally higher as they were motivated to prove that women are equally good, if not better than their male counterparts. Over the years, the performance level has become similar to that of male counterparts.

Cultural and Societal Factors. Cultural and societal norms play a significant role in determining the extent to which women are integrated into the armed services. Some countries, including India, have more traditional gender roles and do face resistance to women’s participation. In Indian society, protecting women from external aggressors is generally considered necessary. Prospects of women falling prey to an enemy as a prisoner of war or a hostage and the threat of physical abuse and torture create an apprehensive about the induction of women in combat units involved in direct contact combat with the enemy. While both male and female prisoners are at risk of torture and rape, there is low acceptance in societies to abuse of women prisoners of war by the enemy. Recent gruesome pictures being circulated in social media about the treatment of Israeli women by HAMAS substantiate this fear and apprehension. The counterargument is that even the male warriors are at times subjected to such gruesome torture, and secondly, women would join voluntarily, being fully aware of these occupational dangers.

Role Models and Leadership. Women have increasingly taken on leadership roles within defence services, including senior-level positions and even as heads of defence ministries in some countries. The presence of women in leadership positions within the defence forces serves as a source of inspiration for aspiring women in the military. It helps reinforce the idea that gender should not limit one’s career options. In the Indian armed forces, Women officers are allowed in combat services and supervisory roles. By 2020, three officers had reached three-star rank in the Medical Services. IAF has already appointed a woman officer as the commanding officer of a frontline combat unit. Indian Army has also cleared about 108 women officers for promotion to the Colonel (select) rank for the first in “combat-support arms” and services like the Corps of Engineers, Signals, Ordnance, EME, and other such branches after granting them permanent commission in the Army. If found suitable and selected, some of them will hold command appointments in the future.

“Arguments founded on the physical strengths and weaknesses of men and women and assumptions about women in the social context of marriage and family do not constitute a constitutionally valid basis for denying equal opportunity to women officers.”

-Supreme Court of India

Legal Interventions. Like many countries, even in India, Women in defence services have knocked on the judicial doors to redress their grievances related to gender equality and opportunities. In 2010, the Delhi High Court granted permanent commissions to women serving as short service commission (SSC) Army and Air Force officers. The Air Force implemented the decision, but the Indian Army appealed against the judgment and approached the Supreme Court. Upholding the 2010 Delhi judgment, the Supreme Court on February 17, 2020, said that women SSC officers are also eligible to get permanent commission in the Army, which till now was only granted to male officers. In the following judgment on March 17, 2020, the Supreme Court said that women SSC officers of the Navy can be granted permanent commission just like their male counterparts in the Indian Navy. In its judgment, the Supreme Court criticised societal stereotypes that discriminate against women based on sex and gender. The Court said we cannot assume that only women have domestic responsibilities toward parenting, children, and family. Permanent commission cannot be denied because of flawed reasons based on the physiological differences between men and women, which portray women as the weaker sex—stressing the need to change social mindsets. The Court held that differentiating women’s abilities based on gender is against the fundamental constitutional right of equality and dignity. Apart from granting eligibility for permanent commission, the Court also addressed the issue of women seeking command positions in the army. The Court said that an absolute restriction on women seeking command appointments is against the constitutional right to equality under Article 14. While deciding whether a particular candidate should be granted a commanding post, one should consider the service needs, performance, and organisational requirements. Command assignments are not automatic for men SSC officers who are granted permanent commission and would not be automatic for women either. However, women cannot be excluded from being considered for command appointments. This judgment also entails that all officers and soldiers go through the same selection criteria – toughness schedule, promotion exams, command criteria assignments, and appointments with no concessions. The Supreme Court has unequivocally stated that women officers who volunteer for combat action must comply with the standards ensured and should not be lowered to make room for women officers. Otherwise, this will compromise the “Operational Effectiveness” of the force.

Policies and Regulations. Countries have different policies and regulations regarding the participation of women in defence services. Some countries, like the United States, have gradually expanded the roles women can serve in, including combat roles, while others have more restrictive policies. Articles 14, 15, 16 and 19 of the Indian constitution uphold the values of equality and allow equal, non-discriminatory opportunities at work. The Indian government has been working on policy changes and reforms to address various challenges and concerns related to the deployment and accommodation of women in defence services. Over the years, there have been significant legal and policy changes aimed at promoting gender equality and enhancing the role of women in India’s defence services. These changes have opened up more opportunities for women to serve in diverse capacities across various branches. It is claimed that employment in the Indian Armed Forces is gender-neutral. There is no distinction in the deployment and working conditions of male and female soldiers in the arms and services they serve. The postings are per organisational requirements, and employment is per qualifications and qualitative service requirements. However, the services try to accommodate personal requirements subject to service needs. Relevant questions that arise during the policy formulation are whether the combat is gender-independent and whether women are as capable (in physical, mental, and psychological domains) as men in combat operations. The policy changes need to consider the changing nature of warfare and the role of technology. Input from serving personnel, veterans (with decades of experience,) and foreign-friendly militaries would be valuable for policy formulation and review. It must be an evolutionary process while balancing personal and organisational aspirations, growth, necessities, and concerns.

Women in Combat Role. Many countries allow women in combat roles. The United States, Israel, North Korea, France, Germany, Netherlands, Australia, Norway and Canada are among the global militaries that employ women in front-line combat positions. The United States allowed women to serve in combat roles in 2013. Some countries now allow women to serve in infantry, artillery, armoured, and even Special Forces units. Globally, the number of women in combat roles is low due to an inadequate number of volunteers and, secondly, their inability to meet the selection criteria. Combat roles in the Indian Armed Forces have long been an exclusive domain for men. In recent years, India has opened combat and operational roles to women. In 2015, the Indian Air Force, for the first time, decided to induct women into the fighter wing. The Indian Navy followed suit, with the first naval women commissioned as pilots of the Maritime Reconnaissance Aircraft in 2016. Currently, 18 women are flying fighters like MiG-21s, MiG-29s, Sukhois, and new Rafales in the IAF, and there are also over 145 women helicopter and transport aircraft pilots. Indian Navy has deployed 30 women officers on frontline warships and plans to give them more opportunities to serve on warships. Indian Army has enabled women to operate helicopters, and earlier this year, the first five women officers were also commissioned into the artillery regiments and are now being trained to handle howitzers and rocket systems.

Special Forces. Special Forces (Para-SF of the Indian army, Marine Commandos of the Navy, and Garud Commando Force of IAF) are specially trained units, equipped with specialised weapons, deployed for clandestine warfare or special operations like counter-terrorism, anti-hijack, hostage rescue, intelligence-gathering, surgical strikes, and covert operations behind enemy lines. The voluntary force undergoes extremely arduous physical and mental training. Women officers in the armed forces are eligible to volunteer for induction into the Special Forces without gender bias, provided they meet selection qualitative requirements (QRs) and complete the training. A few women have volunteered to join the Special Forces, with some selected to undergo the training. So far, none have succeeded in completing the training. It is a matter of time before even this glass ceiling is broken.

Challenges. Women in the armed forces have made significant progress in many countries, but they still face several challenges due to the historically male-dominated nature of these institutions. The expansion of roles and increased recognition of women’s contributions in the armed forces of India has paved the way for a more inclusive and diverse armed forces in India. Despite these advancements, women in the armed forces can face unique challenges due to prevailing societal norms and gender biases. Although the number of occurrences may be rare, a few women in the armed forces at times may face challenges such as stereotypes, lack of acceptance from male colleagues or subordinates, unequal opportunities, harassment, and discrimination. Unfortunately, such incidents get wide publicity, influencing public opinion adversely. It’s important to note that while these challenges exist to varying extents, many countries, including India, are actively working to address them by implementing policies and initiatives that promote gender equality, diversity, and inclusion within the armed forces. Progress is being made, but there is still work to ensure women have equal opportunities and thrive in all roles within defence organisations.

Acceptance, Gender Bias and Stereotypes. Acceptance of women in the military has not been smooth in any country. Every country had to mould the attitude of its society at large, particularly male soldiers, to enhance the acceptability of women in the military. At the beginning of women’s induction, they felt their presence tended to make the environment ‘formal and stiff’. They were unsure where to draw the line in their behaviour and interaction with their male counterparts. Now, one sees a high level of acceptance and ease in each other’s presence. Traditional gender biases and stereotypes can create an unsatisfying environment for women in the armed forces. Some seniors may doubt their abilities or assign them roles based on stereotypes rather than their skills and qualifications. Some women felt that their competence was not recognised in the early years. Despite their technical qualifications, they were generally utilised for perceived women-like jobs. A feeling of being marginalised and not included in the decision-making process also prevailed. This has changed to a considerable extent, and such occurrences are rare.

Physical Fitness Standards. Physical attributes have played a significant role in denying women an active role in combat over the years. Some argue that physical fitness (strength and stamina) standards for specific roles may disadvantage women due to physiological differences. Apprehensions are also voiced about the effect of pregnancy on physical fitness. In modern high-technology warfare, technical expertise and decision-making skills are more valuable than physical strength; however, situations like the Chumar, Doklam and Galwan clash cannot be ignored. Striking a balance between maintaining necessary standards and accommodating gender differences is a matter of debate. The armed forces lay down the physical standard attributes well. These form the basis for selecting an individual for training and continuation in the combat arm afterwards. Gender should not play a role so long one meets the basic physical requirements to be a combatant.

Work-Life Balance. The demanding nature of work in the armed forces, including long deployments and frequent relocations, can make it challenging for women to balance their military duties with family responsibilities. Several women in the armed forces find a life partner within the service. While this has some advantages, it is an organisational challenge for Human Resource managers. It becomes difficult to manage co-location for such couples, and the problem gets accentuated at higher seniorities, mainly if both are of equal seniority and/or from the same branch.

Harassment and Discrimination. Women in the armed forces, like in any other organisation, may experience sexual harassment, gender-based discrimination, or bullying. All Defence services have adequate checks and balances, procedures, and systems (backed by legal provisions) to curb these occurrences. The Indian armed forces follow a policy of zero tolerance for such acts and award severe punishment to the defaulters. Changes in thought processes occur in society and even in the defence service regarding gender-neutral guilt in these matters.

Lack of Support Services. Access to gender-specific support services and infrastructure is another challenge. While it is easy to address this issue at so-called peace locations, it may be a challenge at forward bases with harsh conditions, such as Siachin or a submarine in the Navy, etc.

Way Ahead

“My personal experience has been that the (principles) of leadership and team building apply equally to women as to men. As long as you protect qualification standards and give no impression that anyone is getting a free ride, integration, while not without bumps, will be much less dramatic than people envision.”

-Major Eleanor Taylor

Canadian Military

(The first woman to lead an infantry company in combat).

Women have become a part of the defence services in India. Most of the teething problems have been addressed to a large extent; however, their integration is an evolutionary process. The related policy changes need to consider the changing nature of warfare and the role of technology. Input from serving personnel, veterans (with decades of experience), and foreign-friendly militaries would be valuable for policy formulation and review. It must be an evolutionary process while balancing personal and organisational aspirations, growth, necessities, and concerns. Some suggestions are as follows:-

-

- Lessons could be drawn from the policies and experience of foreign militaries for female enlistment, training, terms and conditions, and management. These best practices should be tailored to our environment.

-

- The policy decisions should be based on facts and realities rather than presumptions and preconceptions.

-

- The rules and standards should be gender-neutral. Armed forces are highly competitive and have a pyramidal structure. Grants of higher ranks and other appointments should be gender-neutral, purely based on merit, and not fixed quotas.

-

- Women officers should be adequately trained to prepare them for combat and command roles and to lead men in peace and war.

-

- Gender-specific or gender-neutral physical fitness standards for men and women should be based on scientific realities. Operational preparedness should not be compromised at the cost of relaxed medical standards. Even timelines should be stipulated for regaining the required fitness levels post-pregnancy like any other gender-neutral medical contingency rules.

-

- Increase acceptance of women in defence services by sensitising and enhancing the awareness levels of society at large and defence establishments in particular.

-

- Aspects related to women in defence services should not be politicised as a vote bank tactic.

-

- Disciplinary standards should not be compromised at any cost. The defaulters should be dealt with appropriately with equal severity.

-

- The work-life balance issues should be accommodated subject to service exigencies.

With future warfighting becoming more sophisticated and technologically advanced, there is a growing need to tap into the large pool of human resources, including women. While women have been inducted into the Indian defence services, their full integration is slow and evolutionary. It is important to note that while progress has been made, there are still challenges to address. The prospects of women in the defence services will depend on continued policy reforms, social change, and the commitment of the defence establishment to provide equal opportunities to both men and women.

Link to the article in the journal:-

Suggestions and value additions are most welcome

For regular updates, please register here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

References

- “Women in Defence Services”, Press Release by Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Defence India, and 17 MAR 2023.

- Gp Capt Kishore Khera (Retd), “COMBAT AVIATION: Flight Path” 1968-2018.

- Manishsiq, “ Women in Armed Forces”, Studyiq, 08 May 23.

- “Women and the Military, Civilsdaily, 18 Jan 22.

- Rajat Pandit, “No woman has yet qualified for military Special Forces, though some volunteered”, The Times of India, 28 Jul 23.

- “Women in Armed Forces”, Clear IAS, 10 Mar 23.

- “Role of women in armed forces”, OHeraldo, 07 Mar 22.

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.

Very apt subject and timely too..!

Great analysis and all aspects covered .

Congratulations..!

Thanks

Excellent round-up of all aspects to do with women in the Armed Forces, Chhotu!

Thanks

Very well researched and put across all the points so methodically- Good Read

Thanks

This is well researched, informative & comprehensive article on women in armed forces, Khosla Sir.

As a veteran & now a startup founder of a women empowerment initiative, Inspire, I find it relevant to share with interested people .

Thanks

great work, thank you for writing this

Thanks