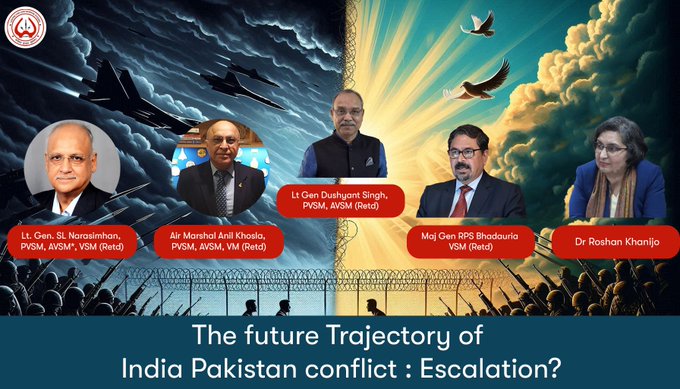

CLAWS conducted a Seminar on “Operation Sindoor” on 08 May 25.

Link to the webinar:-

Please Add Value to the subject with your views and Comments.

For regular updates, please register your email here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

Pics Courtesy: Internet

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.