My Article published on the EurasianTimes website on 01 Jun 25.

India’s quest for self-reliance in defence technology has reached a pivotal milestone with the approval of the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) Programme Execution Model on May 26, 2025. This model, greenlit by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, introduces a collaborative and competitive framework to accelerate the development of India’s first indigenous fifth-generation stealth fighter jet. Designed by the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) under the Ministry of Defence, the AMCA is a 25-tonne, twin-engine, multirole stealth aircraft intended to bolster the Indian airpower capabilities by 2035. The new execution model emphasises private sector involvement, international collaboration, and a competitive bidding process, significantly departing from traditional defence procurement practices.

Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft. AMCA is India’s fifth-generation stealth fighter jet program, developed by the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) under the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). Designed as a multirole, twin-engine aircraft, the AMCA aims to replace ageing fleets such as the SEPECAT Jaguar and Mirage 2000, while complementing the Rafale and future Tejas Mk2 in the Indian Air Force (IAF). The 25-tonne, twin-engine AMCA features stealth shaping, internal weapons bays, and advanced sensor fusion. It is intended to excel in air superiority, deep strike, and electronic warfare missions. It will have an advanced avionics suite, Indigenous AESA radar, and potentially AI-based mission systems. The aircraft is envisioned in two phases: Mark 1 with current-generation technologies and imported engines, and Mark 2 incorporating Indigenous sixth-generation features and an Indian powerplant. The AMCA is strategically significant as it will enhance India’s air combat capabilities and reduce reliance on foreign platforms.

Strategic Significance of AMCA. The AMCA is not just a defence project but a strategic lever and India’s entry ticket into the elite club of fifth-generation fighter operators. The AMCA program is critical to countering regional threats, particularly from China and Pakistan. China’s deployment of J-20 and J-35 stealth fighters, with plans to supply 40 J-35s to Pakistan, underscores the urgency of AMCA’s development. The IAF’s modernisation drive, aiming for 42 squadrons by 2035, relies on the AMCA to maintain a technological edge. The collaborative model’s success could position India among the elite nations with fifth-generation fighters, alongside the US, China, and Russia.

Historical Progress: Bottlenecks. The AMCA program was conceived in the early 2010s as a follow-on to the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas. However, despite its strategic importance, progress was tepid due to multiple challenges. Initial timelines projected a first flight by 2020 and production by 2025, but these slipped to 2028 and 2038-39 due to funding constraints and bureaucratic delays. The program’s preliminary design phase began in 2015, with CCS approval only in 2024. The Tejas program’s prolonged development (from the 1980s to the late 2010s) is a cautionary tale, highlighting systemic issues in India’s defence ecosystem. The program lacked an empowered governance structure, slow decision-making, and HAL’s overburdened capacity. The absence of an indigenous high-thrust engine has been a persistent hurdle for the program; the Kaveri engine program’s inability to meet requirements forced reliance on foreign engines, delaying self-reliance. India lacked expertise in advanced technologies and high-thrust engines, necessitating foreign collaboration. The withdrawal from the Indo-Russian FGFA project in 2018 due to disagreements over technology transfer forced a fully indigenous approach, increasing technical risks. The new execution model addresses many of these issues by decentralising authority, attracting capital, and professionalising development.

Boosting the AMCA Program

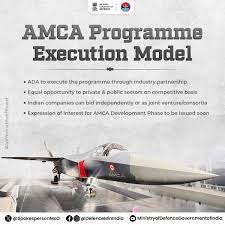

Collaborative Execution Model. Announced on May 26, 2025, the AMCA Programme Execution Model introduces a public-private partnership (PPP) framework, moving away from the traditional reliance on Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) as the sole manufacturer. The new model proposes a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV)-based framework, with a private sector partner who will work alongside the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), and the Indian Air Force (IAF). Under this model, the ADA will issue an Expression of Interest (EoI) to public and private entities, allowing them to bid independently or as consortia. The model offers flexibility to include global OEMs as technology partners or equity stakeholders in the SPV. This shift signifies a bold experiment breaking free from India’s traditionally state-dominated defence production ecosystem. It promises to enhance project accountability, bring commercial rigour to execution, and facilitate foreign direct investment and technology infusion. The competitive approach aims to streamline development, reduce costs, and integrate cutting-edge technologies. One of the most progressive steps is to move from a nomination-based to a competitive merit-based selection model. The collaborative model is expected to provide several key benefits to the AMCA program.

Encouraging Efficiency and Speed. By involving private sector firms alongside HAL, the model diversifies the production base, reducing bottlenecks associated with a single manufacturer. Private companies would bring agility, innovation, and financial muscle, which can accelerate manufacturing and delivery timelines. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) has emphasised reducing timelines. Firms will be incentivised to optimise costs and timelines to win bids, reducing the bureaucratic delays that plagued earlier phases of the AMCA program. The Combined Quality Cum Cost Based System (CQCCBS) model will evaluate bids based on technical and financial merits, ensuring high-quality outcomes.

Technology Integration. Including private firms would enable access to advanced manufacturing techniques and expertise in composites, avionics, and AI. The collaboration is expected to enhance the AMCA’s technological edge, aligning it with global fifth-generation standards.

Economic and Industrial Growth. The model would foster a robust domestic aerospace ecosystem, generating employment and technological advancements. By distributing work packages among private firms, the program stimulates investment in infrastructure and skilled workforce development, aligning with India’s “Atmanirbhar Bharat” vision for self-reliance.

Risk Mitigation. The collaborative approach spreads financial and technical risks across multiple stakeholders, reducing the burden on HAL and the government. This is particularly crucial given the program’s history of delays and funding shortages.

Technological Challenges

However, challenges remain. Establishing fighter jet manufacturing facilities requires significant investment, and private firms may face hurdles in acquiring land, infrastructure, and skilled labour. Scepticism persists about their ability to match HAL’s experience, which could lead to initial teething issues. The AMCA’s development involves overcoming significant technological hurdles, particularly in stealth and engine capabilities.

Stealth Technology. Achieving a low radar cross-section (RCS) is critical for the AMCA’s fifth-generation credentials. The AMCA incorporates a twin-tail layout, platform edge alignment, and diverterless supersonic inlet (DSI) with serpentine ducts to conceal engine fan blades. However, refining radar deflection capabilities is essential. India is developing RAM to reduce RCS, with IIT Kanpur’s Anālakṣhya Meta-material Surface Cloaking System (MSCS) enhancing stealth against Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). Scaling this technology for industrial production remains a challenge. Stealth design compromises aerodynamics, reducing manoeuvrability. Balancing these aspects requires advanced computational modelling and wind-tunnel testing.

Engine Capabilities. The AMCA’s supercruise and thrust vectoring requirements demand a high-thrust engine, posing significant challenges. India’s lack of indigenous jet engine technology remains a bottleneck. Achieving sustained supersonic flight without afterburners and enabling thrust vectoring for enhanced manoeuvrability requires advanced engine designs. Integrating these systems into the AMCA’s airframe is technically demanding. The Kaveri engine project highlighted the gaps in materials science and manufacturing precision, necessitating foreign expertise.

International Collaboration

The AMCA program’s success hinges on robust private sector and international partners participation. Opening the doors to foreign OEMs and global collaboration is a key differentiator of the new model. Foreign OEMs from Russia, France, the UK, and the US are expected to play a crucial role, particularly in addressing technological gaps. Several roles are envisioned for global partners.

Collaborations ensure technology transfer, critical for building India’s aerospace capabilities. Technology transfer is expected, particularly for stealth shaping, radar-absorbing materials (RAM), advanced avionics, and sensors. Foreign partners can provide expertise in radar-absorbing materials, low-observable designs, and AESA radar systems. The US, with its F-35 program, and Russia, with the Su-57, offer valuable insights, though India’s withdrawal from the Indo-Russian FGFA project in 2018 underscores its focus on indigenous control.

India lacks an indigenous jet engine for the project. The AMCA Mk-1 will use GE Aerospace F414 engines (98 kN), while the Mk-2 requires a 110-120 kN engine. France’s Safran is in advanced talks for co-development, leveraging offset obligations from the Rafale deal. Rolls-Royce has offered to co-design and co-develop, allowing India to retain IP rights. Russia’s expertise in thrust vectoring and the US’s advanced engine technologies are also under consideration. Collaboration with GE (U.S.), Safran (France), or Rolls-Royce (UK) is vital.

Implications for HAL: From Monopoly to Competition

HAL, long seen as India’s defence aviation behemoth, now faces a significant paradigm shift. While HAL will remain a stakeholder in the AMCA program, it will no longer enjoy uncontested leadership. Its role is expected to evolve from sole integrator to collaborator, contributing expertise in production, system integration, and testing infrastructure. This transformation could prove beneficial if HAL adapts proactively. However, the threat of being sidelined if it fails to remain competitive could motivate internal reforms, increase efficiency, and push HAL toward greater innovation and collaboration. Including foreign OEMs and private firms in the AMCA program will have profound implications for HAL.

Shift from Monopoly to Competition. HAL’s role as the default manufacturer is no longer guaranteed. It must now bid alongside private giants, which could challenge its dominance but also push it to improve efficiency and innovation.

Technology Transfer Opportunities. Collaboration with foreign OEMs like Safran (France) and Rolls-Royce (UK) for engine development offers HAL access to advanced technologies. However, HAL must navigate intellectual property (IP) agreements to ensure India retains significant control.

Capacity Constraints. HAL’s current workload strains its resources, including 180 Tejas Mk-1A aircraft and four Tejas Mk-2 prototypes. The competitive model would allow HAL to focus on core competencies like final assembly while outsourcing subassemblies to private firms, potentially alleviating pressure.

Challenges Ahead

While the execution model marks a shift, several hurdles remain.

-

- SPV Selection & Governance. Choosing the right private partner with financial depth, technical competence, and political neutrality is critical.

-

- IP Ownership. Managing intellectual property rights, especially with foreign OEMs, will require legal finesse.

-

- Funding Certainty. The AMCA requires an estimated ₹15,000–20,000 crore for development. Ensuring uninterrupted funding from all stakeholders will be vital.

-

- Workforce & Skill Gaps. India’s aerospace talent pool must scale up to meet the design, integration, and production demands.

-

- Export Potential. Safeguards and foreign collaboration agreements should not hinder India from exporting the platform to friendly nations.

Conclusion

The announcement of a collaborative execution model for AMCA on 26 May 2025 could be the inflexion point the program needed. The model addresses historical delays and technological gaps by fostering competition, involving private firms, and leveraging international expertise. While HAL’s role remains pivotal, shifting toward a diversified production base could redefine India’s defence manufacturing landscape. For a nation striving for strategic autonomy, technological self-reliance, and regional superiority, the success of the AMCA is non-negotiable. However, its execution depends on how well India can manage the complex dynamics of competition, collaboration, and capability development. If the SPV model succeeds, it could become the blueprint for all future high-tech defence platforms in India—from UAVs to next-gen submarines.

Please Add Value to the write-up with your views on the subject.

For regular updates, please register your email here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

Pics Courtesy: Internet

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.

References:-

- Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Press Release: “Collaborative Execution Model for AMCA Programme Announced”, 26 May 2025.

- Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA). Overview of the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) Programme.

- Pubby, Manu. “India’s AMCA fighter jet project to get private sector partner.” The Economic Times, May 2025.

- Unnithan, Sandeep. “How AMCA Will Shape India’s Future Air Power.” India Today Defence, April 2025.

- Raju, R. “Challenges in India’s Military Jet Engine Development.” ORF Occasional Paper No. 404, Observer Research Foundation, 2024.

- Joshi, Manoj. “India’s Quest for Strategic Autonomy through Defence Indigenisation.” Centre for Policy Research, 2023.

- DRDO Annual Report 2023–24. Chapter on Aeronautics R&D and Indigenous Fighter Programs.

- GlobalSecurity.org. “AMCA – Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (India).”

- FlightGlobal. “India Eyes Foreign Partners for AMCA Jet Engine Collaboration.” March 2024.

- Vivek, Raghuvanshi. “India’s AMCA Jet to Fly with GE Engine Initially, Indigenous Powerplant Planned Later.” Defence News, July 2024.

- Roy, Shubhajit. “France’s Safran Proposes Joint Development of Jet Engine for India’s AMCA.” The Indian Express, January 2024.

- Singh, Abhijit Iyer-Mitra. “Fifth-Generation Fighter Development: Why India Needs to Rethink.” VIF Brief, Vivekananda International Foundation, 2023.