Presented my paper at the seminar at Dayananda Sagar University, Bangalore on 21 Apr 25.

In an increasingly interconnected world, conflicts are no longer confined to national borders. The impact of wars, social unrest, and political disputes extends beyond individual nations, affecting global security, economic stability, and human rights. In this context, global citizenship emerges as a tool and an empowering force for conflict resolution and peacebuilding. Regardless of nationality, global citizens recognise their shared responsibility in fostering dialogue, promoting human rights, and encouraging sustainable peace. This article explores global citizenship’s critical and empowering role in resolving conflicts and building a more harmonious world.

Understanding Global Citizenship. Global citizenship refers to an awareness of the interconnectedness of people across national, cultural, and economic divides. It involves recognising shared responsibilities for global issues, advocating for human rights, and engaging in social activism to create a more just and peaceful world. Unlike traditional citizenship, which is tied to nationality, global citizenship transcends borders and emphasises collective action for global challenges, including conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

Causes of Conflict in the Modern World

To understand the role of global citizenship in conflict resolution, it is essential to analyse the root causes of conflicts. Common factors include:-

Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Divisions. Deep-seated historical grievances and prejudices often create tensions, leading to violent clashes: nationalist ideologies, sectarianism, and identity-based discrimination further fuel societal divisions and unrest.

Economic Disparities. Widespread poverty, unemployment, and unequal distribution of resources generate frustration and social unrest. Marginalised communities may resort to protests or violence when they lack access to economic opportunities.

Political Instability. Corrupt governance, authoritarian regimes, and weak democratic institutions undermine trust in leadership. This instability can lead to civil wars, insurgencies, or military coups, disrupting peace and security.

Human Rights Violations. Systemic discrimination, oppression, and inequality provoke resistance movements and uprisings. Repressive regimes that curtail freedoms often face mass protests, which can escalate into violent conflicts.

Climate Change and Resource Scarcity. Environmental degradation leads to competition for essential resources like water and arable land. Disputes over shrinking resources often escalate into violent territorial or inter-communal conflicts.

Geopolitical Power Struggles. Superpower rivalries and proxy wars intensify global instability. Nations engage in conflicts to assert dominance, often using smaller states as battlegrounds for ideological and strategic competition.

The Role of Global Citizenship in Conflict Resolution

By addressing Conflict through Global Citizenship, promoting education, advocacy, and cross-cultural dialogue, global citizens can help bridge divides. Supporting diplomacy and sustainable policies fosters long-term peace and conflict resolution.

Promoting Cross-Cultural Understanding and Tolerance. One fundamental way global citizenship aids conflict resolution is by promoting tolerance and intercultural dialogue. Many conflicts arise from misunderstandings, stereotypes, and historical grievances. Through global education initiatives, international exchange programs, and cultural diplomacy, global citizens help bridge divides and encourage mutual respect.

Advocating for Human Rights and Social Justice. Global citizens are crucial in advocating for human rights and challenging injustices contributing to conflict. Organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch raise awareness of human rights abuses and pressure governments and institutions to uphold international norms. By amplifying the voices of marginalised communities, global citizens not only help address the grievances that often lead to conflict but also foster a sense of empathy and compassion in the global community.

Strengthening International Institutions and Multilateral Cooperation. Global governance institutions, such as the United Nations (UN), the International Criminal Court (ICC), and regional organisations like the African Union (AU) and the European Union (EU), play a critical role in conflict resolution. Global citizens support these institutions by advocating for international treaties, peacekeeping missions, and diplomatic initiatives. Civil society groups, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and grassroots activists engage with these institutions to ensure their effectiveness in maintaining global peace.

Engaging in Grassroots Peace Initiatives. While governments and international bodies play a significant role in conflict resolution, local peacebuilding efforts are equally important. Community-based reconciliation programs, interfaith dialogues, and nonviolent resistance movements help prevent and mitigate conflicts at the local level. Global citizens contribute to these efforts by participating in peace education programs, volunteering in conflict-affected regions, and supporting initiatives that empower local peacebuilders. This emphasis on grassroots initiatives is designed to make the audience feel engaged and involved in the peacebuilding process.

Economic Justice and Sustainable Development. Economic inequalities and resource scarcity are major drivers of conflict. Global citizens support fair trade policies, ethical business practices, and sustainable development initiatives that reduce economic disparities. Programs such as microfinance, impact investing, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects create economic opportunities and reduce tensions in conflict-prone areas.

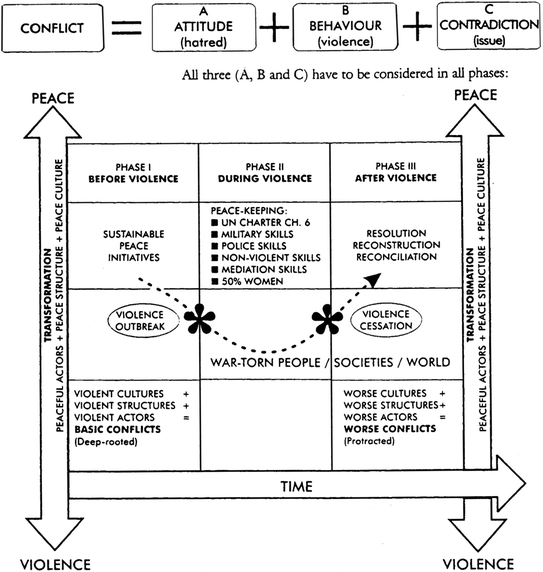

Diplomacy and Conflict Mediation. Diplomatic efforts and mediation are crucial in resolving disputes before they escalate into violence. International organisations, such as the UN and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), often mediate conflicts between nations and communities. Global citizens can engage in diplomatic efforts by supporting negotiation processes, promoting dialogue-based solutions, and advocating peaceful conflict resolution strategies.

Harnessing Technology for Peacebuilding. Technology and social media have become powerful tools for conflict resolution and peace advocacy. Online platforms enable global citizens to mobilise support for peace initiatives, share real-time information about conflicts, and counter misinformation. Initiatives like digital storytelling, peace-focused online campaigns, and artificial intelligence (AI) for conflict prediction have revolutionised peacebuilding efforts worldwide.

Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation. After conflicts subside, rebuilding societies and fostering reconciliation is essential for lasting peace. Global citizens support post-conflict reconstruction efforts by participating in humanitarian aid projects, advocating for truth and reconciliation commissions, and ensuring war-torn regions receive the necessary resources for rebuilding. Programs that reintegrate former combatants into society promote mental health support for war victims and establish memorials to acknowledge past atrocities to help prevent the recurrence of conflicts.

Case Studies: Global Citizenship in Action

The Role of Global Citizens in the South African Reconciliation Process. After decades of apartheid, South Africa’s transition to democracy was facilitated by global advocacy, grassroots activism, and international diplomatic pressure. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) played a significant role in addressing past injustices. Global citizens contributed to this process by supporting anti-apartheid movements, engaging in international sanctions against the regime, and promoting reconciliation initiatives.

The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Global Solidarity. The Syrian civil war displaced millions of people, creating one of the largest refugee crises in modern history. Global citizens responded by advocating for humanitarian assistance, volunteering in refugee camps, and pressuring governments to provide asylum and support. Organisations like the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and grassroots initiatives helped resettle displaced communities and provide essential services.

The Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement, which ended decades of conflict in Northern Ireland, was facilitated by diplomatic negotiations, public engagement, and peacebuilding efforts. International mediators, civil society organisations, and global advocacy groups were crucial in fostering dialogue between conflicting parties. The success of this agreement demonstrates the power of global citizenship in supporting diplomatic and nonviolent conflict resolution.

Challenges to Global Citizenship in Conflict Resolution

While global citizenship plays a crucial role in peacebuilding, it faces several challenges:

Political Resistance. Many governments view global governance mechanisms as threats to national sovereignty and resist international cooperation. Nationalist policies often prioritise domestic interests over global peace efforts, making it difficult to establish common frameworks for conflict resolution. This resistance weakens institutions like the United Nations, limiting their effectiveness in peacebuilding.

Misinformation and Propaganda. The rapid spread of fake news and biased narratives distorts public perception of conflicts, fueling divisions. Governments and interest groups manipulate information to justify aggressive policies, making it harder to foster mutual understanding. Misinformation can erode trust in diplomatic efforts and escalate tensions rather than promote peaceful solutions.

Economic and Political Interests. Nations frequently prioritise economic and strategic interests over peace initiatives, leading to prolonged conflicts. Arms trade, control over resources, and geopolitical rivalries often overshadow humanitarian concerns. Countries may exploit conflicts for economic gain or to expand their influence, undermining global citizenship’s role in promoting stability.

Limited Resources for Peacebuilding. Many peace initiatives suffer from inadequate funding and institutional backing, limiting their impact. Due to financial constraints, international organisations and grassroots movements struggle to sustain long-term peace efforts. Mediation, humanitarian aid, and educational programs cannot effectively address the root causes of conflicts without sufficient support.

Despite these challenges, global citizenship remains vital in fostering peace through advocacy, dialogue, and education. By promoting cross-cultural understanding and supporting grassroots initiatives, individuals and organisations can counter misinformation, pressure governments for ethical policies, and contribute to building a more just and peaceful world.

Conclusion

In an era of globalisation, conflict resolution and peacebuilding require collective action beyond national boundaries. Through education, activism, diplomacy, and economic justice, global citizens play an essential role in addressing the root causes of conflict and fostering lasting peace. By promoting cross-cultural understanding, supporting international institutions, engaging in grassroots initiatives, and leveraging technology for peace, individuals and communities worldwide can contribute to a more just, peaceful, and interconnected world. The future of global conflict resolution depends on global citizens’ commitment to upholding principles of justice, human rights, and sustainable development.

Please Add Value to the write-up with your views on the subject.

For regular updates, please register your email here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

Pics Courtesy: Internet

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.

References:-

- Benhabib, Seyla. “The End of Sovereignty? Global Citizenship and Democratic Attachments.” Public Culture, vol. 19, no. 3, 2007, pp. 27-39.

- Keck, Margaret E., and Sikkink, Kathryn. “Transnational Advocacy Networks in International Politics.” International Organization, vol. 48, no. 4, 1998, pp. 99-120.

- Richmond, Oliver P. “The Dilemmas of Peacebuilding: The Liberal Peace and Beyond.” International Peacekeeping, vol. 16, no. 5, 2009, pp. 74-97.

- Tarrow, Sidney. “The New Transnational Activism.” Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 45-72.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier – Human Development and the Anthropocene. New York: UNDP, 2020.

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education: Preparing Learners for the Challenges of the 21st Century. Paris: UNESCO, 2015.

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Global Governance: Strengthening Multilateralism for Sustainable Peace. Geneva: WEF, 2019.

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Global Order 2025: The Future of International Cooperation. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment, 2018.

- Amnesty International. Annual Report on Human Rights and Global Justice 2022. London: Amnesty International, 2022.

- United Nations Peacekeeping. “The Role of UN Peacekeepers in Conflict Resolution.”

- Oxfam International. The Role of Civil Society in Peacebuilding. Oxfam, 2021.

- The Elders. “A Call for Ethical Leadership in Global Governance.” The Elders, 2022.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.

- Falk, Richard. On Humane Governance: Toward a New Global Politics. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995.

- Kaldor, Mary. New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

- Sen, Amartya. Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.