Pic Courtesy: IPA Journal

News – This week China and Bhutan signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on a Three-Step Roadmap to help speed up long drawn boundary talks.

Bhutan

Bhutan, officially known as the Kingdom of Bhutan is a landlocked country in the Eastern Himalayas. It is bordered by China to the north and India to the south, east and west. Nepal and Bangladesh are located in proximity to Bhutan but do not share a land border. The country has a population of over 754,000 and a territory of 38,394 square km (14,824 sq mi) which ranks 133rd in terms of land area, and 160th in population. Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy with Vajrayana Buddhism as the state religion. Hinduism is the second most dominant religion in Bhutan.

Bhutan’s Priorities

Bhutan has a rich and unique cultural heritage that has largely remained intact because of its isolation from the rest of the world. Bhutanese tradition is deeply steeped in its Buddhist heritage. Because of its largely unspoiled natural environment and cultural heritage, Bhutan has been referred to as The Last Shangri-La.

Bhutan is a country of content people, giving more importance to Gross National Happiness (GNP), rather than GDP. The government’s endeavour is to preserve and sustain the current culture and traditions of the country.

Sino – Bhutan Relations

The Kingdom of Bhutan and the People’s Republic of China do not maintain official diplomatic relations, and their relations are historically tense.

Apart from India, Bhutan is the only country with which China has an unsettled land border and Thimphu is also the only neighbouring country with which Beijing does not have official diplomatic and economic relations.

Tibet factor

Bhutan has had a long and strong cultural, historical, religious and economic connections to Tibet. During the 1959 Tibetan uprising, an estimated 6,000 Tibetans fled to Bhutan and were granted asylum. Bhutan subsequently closed its border to China, fearing more refugees. With the increase in soldiers on the Chinese side of the Sino-Bhutanese border after the 17-point agreement between the Tibetan government and the central government of the PRC, Bhutan withdrew its representative from Lhasa.

Border Dispute

The PRC shares a contiguous border of about 470 km with Bhutan. Bhutan’s border with Tibet has never been officially recognized, much less demarcated. The Republic of China officially claims parts of Bhutan territory as its own. This territorial claim has been maintained by the People’s Republic of China after the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in the Chinese Civil War.

Areas of Dispute

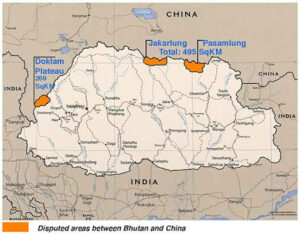

Pic Courtesy: IDR

The Sino-Bhutanese border dispute has traditionally involved 295 square miles (sq mi) of territory, including 191 sq mi in the Jakurlung and Pasamlung valleys in northern Bhutan and another 104 sq mi in western Bhutan that comprise the areas of Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe.

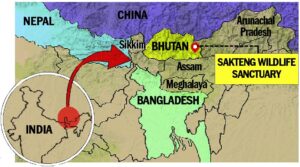

Pic Courtesy: Tribune

China has recently expanded its territorial claims beyond the disputed regions in northern and western Bhutan. It has added territorial claims in Sakteng area in eastern Bhutan, adjoining the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The disputed territory in northern and western Bhutan is relatively small as compared to the new Chinese claim in eastern Bhutan of about 2,051 miles (11 percent of Bhutan’s total area).

China’s Belligerence

Over the years, the Sino-Bhutanese border dispute has become more complicated, with China escalating its claims and taking forceful steps to change the status quo on the ground.

In addition to expanding its territorial claims, China unilaterally has been changing the status quo on the ground through an array of measures, ranging from sending Tibetan grazers and military patrolling teams into disputed areas to building roads and even military structures in contested territory.

Beijing is following its South China Sea strategy in Bhutan as well i.e. push territorial claims and change the demography by creating settlements and bringing civilian population.

Border Talks

Two countries have been engaged in border talks since 1984. They have held over 24 rounds of boundary talks and 10 rounds of negotiations at the ‘Expert Group’ level, in a bid to resolve the dispute.

Two agreements—one on the guiding principles on the settlement of the boundary issues reached in 1988, and the other on maintaining peace and stability in the China-Bhutan border area reached in 1998, provide the basis of the ongoing negotiations.

The disputed territories have been discussed during the past 24 rounds of border talks and included in a “package deal” dispute resolution proposal that China put to Bhutan in 1996. Under this deal, the PRC offered to renounce its claims to the Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys in northern Bhutan in return for Thimphu ceding territory in Doklam to Beijing.

India’s Concern

The border dispute between Bhutan and China has repercussions for India.

Doklam Area. Doklam Plateau has strategic significance. The plateau is located on the southeast side of the trijunction area. It is an important area between the Chumbi Valley on Chinese side and Siliguri corridor (Chicken’s neck) on Indian side. Control of this area gives an advantage to the side controlling it.

Sakteng Area. China’s most recent territorial claim in Sakteng is also of strategic value. The area adjoins the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which contains disputed territory between China and India. Tawang, a key bone of contention between India and China in the eastern sector of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), lies to Sakteng’s northeast.

Analysis (Personal Views)

- Resolution of border dispute with China has a direct bearing on Indian interests.

- Chinese desire to control Doklam and Sakteng areas could be with India in mind.

- China earlier tried to exchange northern territories in exchange of territory in Doklam.

- Sakteng has been added due to interest in Tawang area.

- China has been earlier offering a package deal including aspects like trade and cultural exchange besides resolution of territorial dispute.

- Bhutan sees the package deal as an opening of window for Chinese to make inroads into Bhutan.

- Bhutan is wary of, long term effects of Chinese presence on her culture and values.

- However, younger generations in Bhutan are willing to experiment on engagement with China.

- India and Bhutan have a very good relations with each other.

- The details of contents of the MoU and the three step roadmap are not available in the open domain.

- India needs to keep a close watch on these developments.

- India needs to work closely with Bhutan for resolution of territorial dispute on mutually beneficial terms.

After Thought

Bhutan should be made to realise that agreeing to Chinese terms (if they get tempted) would not guarantee China getting off her back. China has been known for demanding more and more.

Suggestions and value additions are most welcome

For regular updates, please register here

References

https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/bhutan-china-sign-mou-on-boundary-issue-india-wary-324614

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhutan