My Article published in the Chanakya Diaries (Inaugral issue of Chanakya Forum Journal)

Introduction

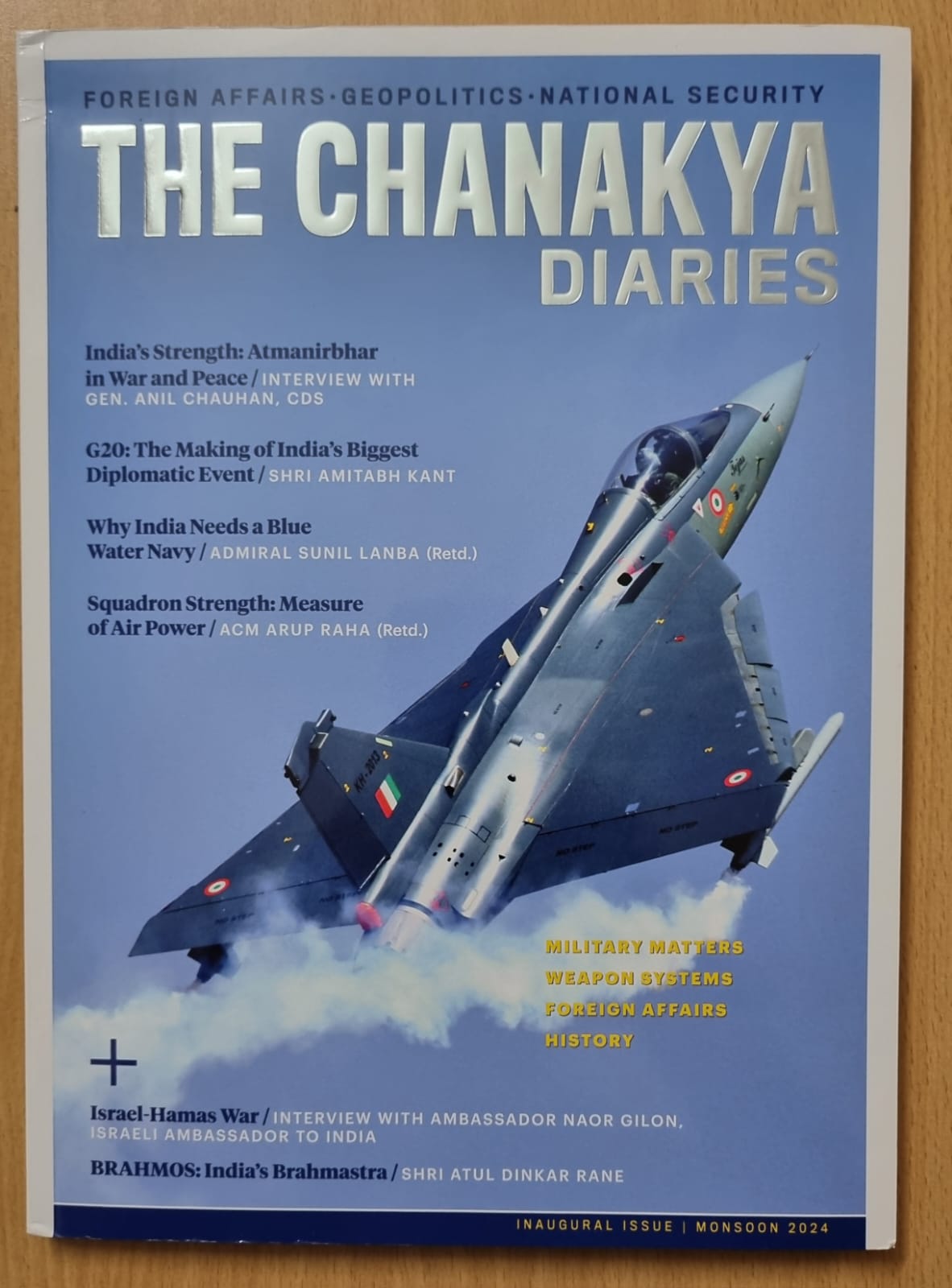

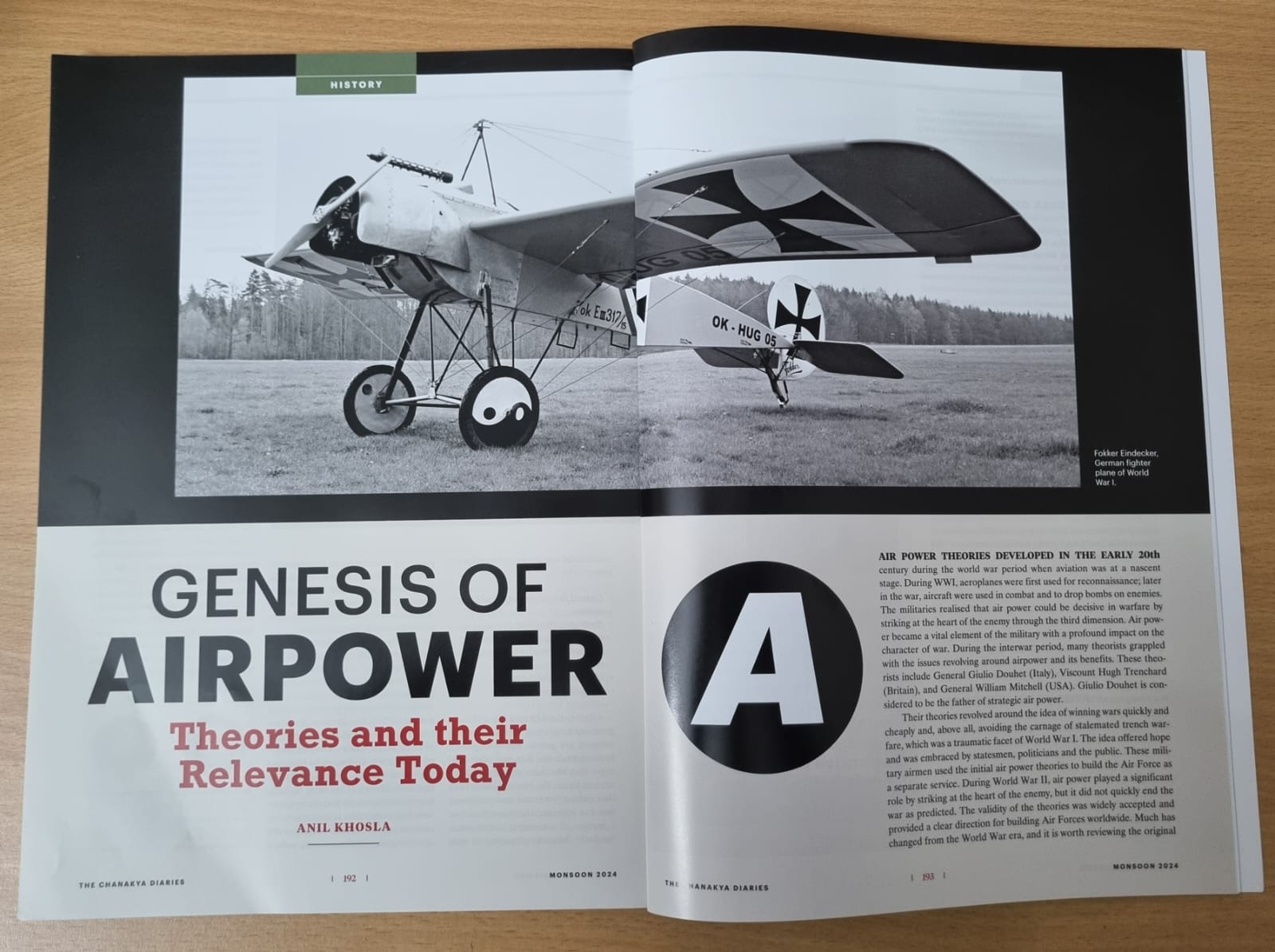

Air power theories developed in the early 20th century during the world war period when aviation was at a nascent stage. During WWI, aeroplanes were first used for reconnaissance; later in the war, aircraft were used in combat and to drop bombs on enemies. The militaries realised that air power could be decisive in warfare by striking at the heart of the enemy through the third dimension. Air power became a vital element of the military with a profound impact on the character of war. During the interwar period, many theorists grappled with the issues revolving around airpower and its benefits. These theorists include General Giulio Douhet (Italian), Viscount Hugh Trenchard (British), and General William Mitchell (American). Giulio Douhet is considered to be the father of strategic air power.

Their theories revolved around the idea of winning wars quickly and cheaply and, above all, avoiding the carnage of stalemated trench warfare, which was a traumatic facet of World War I. The idea offered hope and was embraced by statesmen, politicians and the public. These military airmen used the initial air power theories to build the Air Force as a separate service. During World War II, air power played a significant role by striking at the heart of the enemy, but it did not quickly end the war as predicted. The validity of the theories was widely accepted and provided a clear direction for building Air Forces worldwide. Much has changed from the WW era, and it is worth reviewing the original theories to ascertain their validity, maybe with appropriate adaptations.

Airpower Theorists

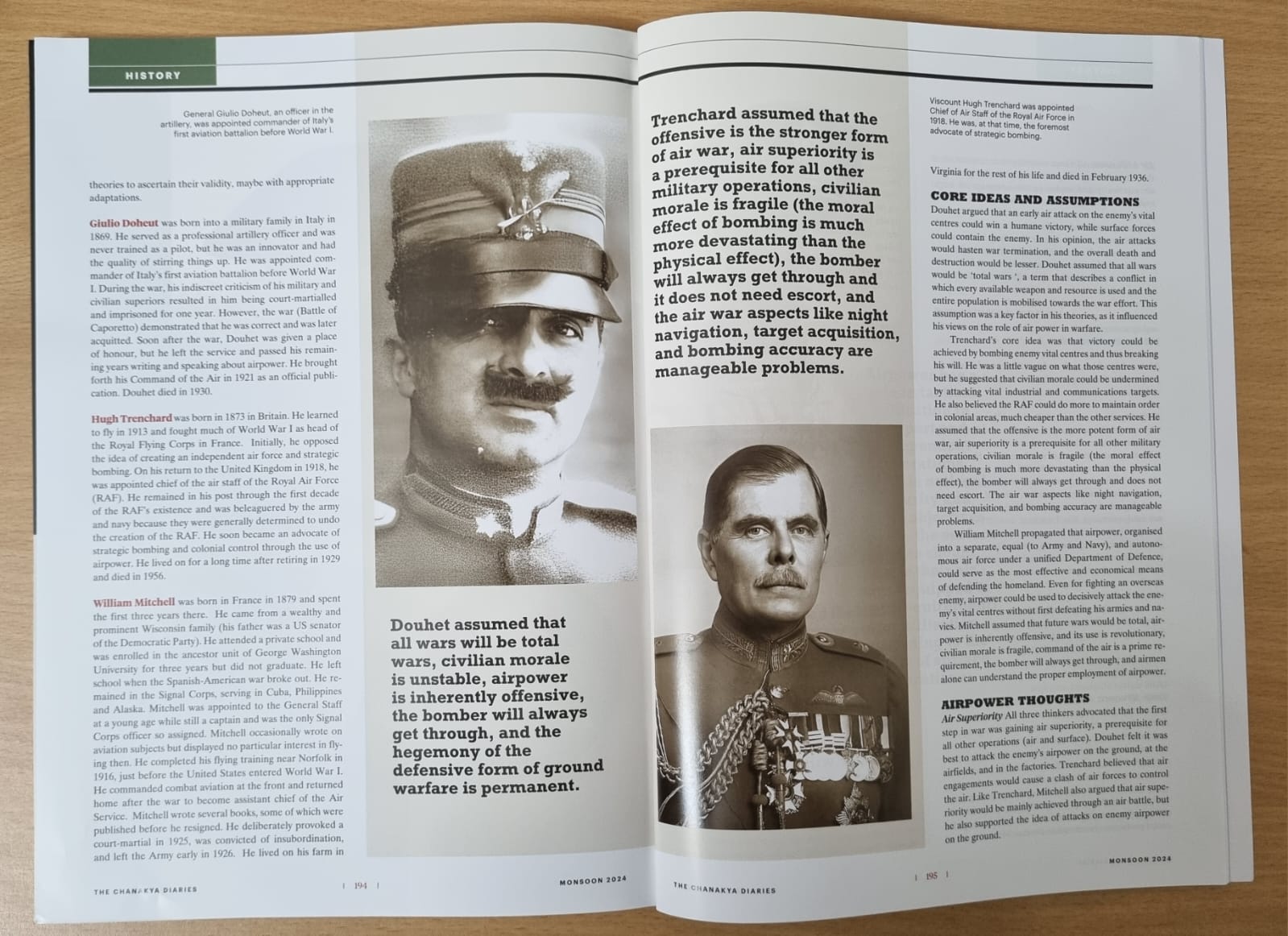

Giulio Doheut. Giulio Doheut was born into a military family in Italy in 1869. He served as a professional artillery officer and was never trained as a pilot, but he was an innovator and had the quality of stirring things up. He was appointed commander of Italy’s first aviation battalion before World War I. During the War, his indiscreet criticism of his military and civilian superiors resulted in him being court-martialled and imprisoned for one year. However, the war (Battle of Caporetto) demonstrated that he was correct and was later acquitted. Soon after the war, Douhet was given a place of honour, but he left the service and passed his remaining years writing and speaking about airpower. He brought forth his Command of the Air in 1921 as an official publication. Douhet died in 1930.

Hugh Trenchard. Hugh Trenchard, a British theorist, was born in 1873. He learned to fly in 1913 and fought much of World War I as head of the Royal Flying Corps in France. Initially, he opposed the idea of creating an independent air force and strategic bombing. On his return to the United Kingdom in 1918, he was appointed chief of the air staff of the Royal Air Force (RAF). He remained in his post through the first decade of the RAF’s existence and was beleaguered by the army and navy because they were generally determined to undo the creation of the RAF. He soon became an advocate of strategic bombing and colonial control through the use of airpower. He lived on for a long time after retiring in 1929 and died in 1956.

William Mitchell. William Mitchell was born in France in 1879 and spent the first three years there. He came from a wealthy and prominent Wisconsin family (His father was a US senator of the Democratic Party). He attended a private school and was enrolled in the ancestor unit of George Washington University for three years but did not graduate. He left school when the Spanish-American war broke out. He remained in the Signal Corps, serving in Cuba, Philippines and Alaska. Mitchell was appointed to the General Staff at a young age while still a captain and was the only Signal Corps officer so assigned. Mitchell occasionally wrote on aviation subjects but displayed no particular interest in flying then. He completed his flying training near Norfolk in 1916, just before the United States entered World War I. He commanded combat aviation at the front and returned home after the war to become assistant chief of the Air Service. Mitchell wrote several books, some of which were published before he resigned. He deliberately provoked a court-martial in 1925, was convicted of insubordination, and left the Army early in 1926. He lived on his farm in Virginia for the rest of his life and died in February 1936.

Core Ideas and Assumptions

Douhet. Douhet argued that an early air attack on the enemy’s vital centres could win a humane victory, while surface forces could contain the enemy. In his opinion, the air attacks would hasten war termination, and the overall death and destruction would be lesser. Douhet assumed that all wars would be ‘total wars ‘, a term that describes a conflict in which every available weapon and resource is used, and the entire population is mobilised towards the war effort. This assumption was a critical factor in his theories, as it influenced his views on the role of air power in warfare.

Trenchard. Trenchard’s core idea was that victory could be achieved by bombing enemy vital centres and thus breaking his will. He was a little vague on what those centres were, but he suggested that civilian morale could be undermined by attacking vital industrial and communications targets. He also believed the RAF could do more to maintain order in colonial areas, much cheaper than the other services. He assumed that the offensive is the more potent form of air war, air superiority is a prerequisite for all other military operations, civilian morale is fragile (the moral effect of bombing is much more devastating than the physical effect), the bomber will always get through and it does not need escort. The air war aspects like night navigation, target acquisition, and bombing accuracy are manageable problems.

William Mitchell. William Mitchell propagated that Airpower, organised into a separate, equal (to Army and Navy), and autonomous air force under a unified Department of Defence, could serve as the most effective and economical means of defending the homeland. Even for fighting an overseas enemy, airpower could be used to decisively attack the enemy’s vital centres without first defeating his armies and navies. Mitchell assumed that future wars would be total, airpower is inherently offensive, and its use is revolutionary, civilian morale is fragile, command of the air is a prime requirement, the bomber will always get through, and airmen alone can understand the proper employment of airpower.

Airpower Thoughts

Air Superiority. All three thinkers advocated that the first step in war was gaining air superiority, a prerequisite for all other operations (air and surface). Douhet felt it was best to attack the enemy’s airpower on the ground, at the airfields, and in the factories. Trenchard believed that air engagements would cause a clash of air forces to control the air. Like Trenchard, Mitchell also argued that air superiority would be mainly achieved through an air battle, but he also supported the idea of attacks on enemy airpower on the ground.

Air Utilisation. All three theorists were unanimous in their thoughts regarding achieving command of the air/air superiority and exploiting the advantage to target civilian morale. They differed a little bit in the targeting philosophy to achieve it. Douhet felt that the mere act of gaining command might be enough. The enemy’s vulnerability would be so great that their leaders would soon capitulate. If not, attacks on the cities and other vital targets would force the leadership to give way. He wanted to attack the people directly, while Trenchard tried to achieve it indirectly by destroying infrastructure targets. Likewise, General Mitchell advocated operations against vital centers, vaguely described as industrial, infrastructure, and agricultural assets, the loss of which would lead to the collapse of civilian morale.

More ink has been spilt and passion expended over the proper selection of targets than over any other airpower subject.

Targeting. In the words of Douhet, “The selection of objectives, the grouping of (attack) zones, and determining the order in which they are to be destroyed is the most difficult and delicate task in aerial warfare”. He felt that no hard and fast rules could be laid down on this aspect of aerial warfare because the choice of enemy targets will depend upon several circumstances, material, moral, and psychological, the importance of which, though real, is not easily estimated. For Trenchard, as with Douhet, the timing of operations for air superiority took precedence. Trenchard’s targeting scheme against morale was vague, but he insisted on following international law, limiting collateral damage, selecting targets in urban areas for their military significance, and attacking vital centers in the infrastructure and production systems. Mitchell was opposed to targeting civilians directly and generally advocated breaking their morale through the destruction of other vital centers like industry, infrastructure, or even agriculture. He did not dwell too much on strategic targets as we know them today. He was more concerned with tactical functions, concentrating mainly on maritime targeting.

Force Structure (Platforms and Weapons). Douhet’s recommendations regarding force structure were more from an Italian perspective. Keeping in mind the geography and affordability. He suggested a strategic air force structure for the other nations that could afford it (like the United States). He felt that only one type of aeroplane was required, the battle plane. For self-protection, these aeroplanes must have moderate speed, long range, and heavy armour. These planes could be armed with self-defence weapons and embedded in the strike package for escort protection. In contrast to Douhet, Mitchell believed no single type of aeroplane was adequate. At first, he advocated a preponderance of pursuit (By Fighter aircraft) but then increasingly emphasised the need for more bomber units. Douhet and Mitchell believed that the bombers would have to combine high explosive and incendiary and gas bombs to have a synergistic effect. Mitchell also placed some emphasis on big bombs (500 to 2000-pounders) and even on aerial torpedoes and radio-controlled guided missiles. Trenchard always felt that the fighter aircraft had a significant role in the air war. However, after World War I, he prioritised bomber units (two-engine types to four-engine aircraft).

Reorganisation. Douhet argued that surface forces would employ airpower as an auxiliary to them. He advocated organising airpower under a separate air force and using it as an independent force to achieve victory without needing tactical victories on the land and at sea. Trenchard initially opposed (though not as adamantly) creating a single air arm but later became more firmly committed to a separate air force. Trenchard strived to retain the RAF with all airpower centralised under its command. He emphasised that the unified control of airpower was essential for achieving the primary objective of gaining and maintaining air superiority over land and sea. On his recommendation, Britain proceeded with the idea of a separate air ministry and a separate air force, but without a formal organisation above to control all three services. Mitchell endorsed the concept of a centralised command of airpower under a separate and independent air force and created a unified Department of Defence. He asserted that only an airman could have the vision of the proper role of airpower; therefore, all military aviation should fall under the direct control of such an airman.

Joint Warfare. Douhet asserted that the other armed forces would only stand on the defensive until the air force offensive had been quickly decisive. On the other hand, Trenchard was well indoctrinated in ground warfare, having been an army officer himself. While World War I was still being fought, he was firm in his commitment to ground support and allowed only that “excess” aircraft could be dedicated to independent operations. After the war, though, Trenchard increasingly argued that the role of the British army and navy was secondary, and the role of the RAF and strategic attack was primary. Trenchard, although favoured independent operations, made a greater allowance than Douhet for cooperation with other services in operations against the enemy’s fielded forces. Mitchell stressed that the Air Force would have to be a primary military instrument of war and saw a place for independent missions for air forces well beyond the battlefield.

Relevance Today

Core Ideas. All three airpower theoreticians were propagating a separate Air Force’s viability and ability to end the war quickly and humanely. Their thoughts (about humane victory) were that air power would make the conflict termination faster, and overall, death and destruction would be comparatively lesser. War itself can never be humane. The death and destruction is the method of the war. Over the years, mankind has gone on to develop weapons of mass destruction, although the trend these days is for reduced tolerance to the loss of human life. Warfare is changing, wherein resorting to terror is becoming a norm, and terror strives for the loss of human life not only during hostilities but even during peacetime.

Beliefs.

-

- Their belief that the coming of aviation was revolutionary has proved to be true. Over the years, airpower has revolutionised the way wars are fought. Several roles and tasks have been assigned to airpower. These are performed not only during war but also during peacetime and no-war, no-peacetime situations.

-

- Their presumption that all wars will be total wars has been proven right. Warfare has become multi-domain, with the inclusion of new domains of warfare (cyber, space, electronic and information). Grey zone warfare has become a norm, with everything and anything being used as a weapon.

-

- Their assumption that civilian morale is unstable and fragile has not been correct. Human will has lots of resilience and is not easy to break. History is replete with examples of attacks that have strengthened the will instead.

-

- Their insight that airpower is inherently offensive during hostilities is true in some sense. Also, it has been proven that an offensive approach is a better option, even for air defence operations. However, airpower has many roles and tasks (Military Diplomacy, Strategic Coercion, Signalling, Human Assistance and Disaster Relief, aid to Civil authorities, etc.) that are not necessarily offensive.

-

- The three theoreticians also believed that the bomber would always get through, it does not need an escort, and anti-aircraft weapons are ineffective in preventing enemy attacks. These assumptions have been far from true. The survivability of bombers in contested airspace is doubtful, and not only bombers but even platforms like fixed-wing transport aircraft, helicopters and drones are vulnerable. They need a certain degree of air superiority and fighter protection under AWACS/AEWC aircraft coverage. Anti-aircraft weapons have evolved over the years with enhancements in their effectiveness. Recent wars have demonstrated the vulnerability of helicopters and fixed-wing transport aircraft to shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles.

-

- Night navigation, target acquisition, and bombing accuracy are manageable problems. These predictions have come true. Weapons have become smarter, with capabilities like stand-off, precision, fire and forget, all-weather, multiple warheads, etc.

Joint Airpower Utilisation. The military thinkers were right that airpower has a lot of potential beyond tactical employment. Airpower has a role in tactical utilisation in support and independent operations towards national security and objectives. Ideally, the surface forces should have their air arm (equipped to their requirement) for utilisation according to the tenets of surface operations. This would be ideal (e.g., the USA has four air arms, USAF, US Army aviation, US Navy air arm, and US Marines). However, it is not achievable by all due to affordability (air assets are costly to procure and maintain). The next best solution, therefore, is the centralised placing of air assets and the conduct of operations with joint planning and execution. Each force has its defined roles, tasks and core competencies. Warfare has evolved into a complex activity wherein no service alone can achieve national or military objectives. It has to jointly coordinate efforts with a proper understanding and utilisation of their respective strengths and core competencies. The warfare is no longer restricted to the domain of the military. It necessitates a coordinated effort by all the means of statecraft. Even the military-civil fusion has become extremely important.

Orchestration of Air War. The three scholar warriors were correct in their belief that using air power and orchestrating air war is a complex subject that is not easily comprehensible. Orchestrating an air war has become both a science and an art, with many imponderables and factors to be considered. Over the years, some guidelines have been articulated. Gripping these and choosing enemy targets constitutes what may be defined as an aerial strategy. These aspects are best understood by airmen directing the air war.

Targeting. The offensive application of airpower essentially revolves around targeting. Early airpower theories advocated attacks on vital centres to break the enemy’s morale and will to fight. Many scholars feel they were vague on targeting and left an impression of sequential warfare. An early attack on the enemy’s vital centres to commence hostilities has become a norm. Still, to create destruction, disruption, chaos and confusion. Subsequent attacks depend upon the national, military, service, strategic and tactical objectives. Airpower allows parallel operations, conducting various campaigns simultaneously. Commanders (of both independent air forces and joint forces) have to decide on the allocation of percentages of air effort towards different campaigns being run concurrently. Also, dynamic changes can be made depending on the developing situation. A carefully prepared joint target list is a prerequisite to any air campaign planning.

Air superiority. The theory that “command of the air is a prime requirement and air superiority is a prerequisite for all other military operations” has changed. Over the years, terms like air dominance, command/control of the air, air supremacy, air superiority, limited air superiority, and favourable air situation have been included in the lexicon of air analysts and strategists. These are generally used interchangeably but have a subtle difference and connotation. Achieving air superiority has a lot of advantages but does not guarantee a victory on its own; it has to be exploited to gain victory. Command/Control of the air is still a very relevant strategy/theory. However, the degree of achievement (air supremacy, air superiority and favourable air situation) varies depending upon the disparity between the opposing forces and the effectiveness of the counter-air campaign. The most desirable method is to obtain air superiority by attacking the enemy’s airpower on the ground. However, alternative means have evolved over the years for its achievement (attack on enemy aircraft on the ground, operating surfaces, attack on storage facilities and supply chain of crucial aviation enabling supplies and reliance on AD weapons, etc.). Another aspect is that the commencement of surface operations has been delinked from the earlier concept of sequential warfare, wherein surface operations commenced after the dedicated air superiority counter-air campaign.

Force Structure. Initially, the focus of airpower was mainly on strategic bombing and the achievement of air superiority. The force structure of the newly formed air forces consisted of bombers and fighter aircraft for their protection and air defence purposes. Over the years, newer specialist platforms, systems, and weapons have been added to the inventory. Specialist aircraft (fixed wing and helicopters) for close air support to the surface forces were used for some time. However, with the proliferation of shoulder-fired AD weapons, their efficacy has become doubtful. Secondly, the trend is to develop and maintain a fleet of swing-role, multi-role, and omni-role aircraft. The force structure of a potent air force now contains multi-role fighter aircraft, combat support fixed wing and rotary wing aircraft (AWACS, Aerial Refuellers, Air transport aircraft, particular operation aircraft, variety of helicopters), unmanned platforms, an array of smart weapons (for ground attack, air combat and air defence), long-range vectors (surface to surface missiles including hypersonic weapons), radars, air operation enabling systems, and networks. The trend is to include swarms of drones and a combination of manned and unmanned platforms (loyal wingman concept).

Conclusion

Douhet, Trenchard, and Mitchel’s contributions towards air power theory and their efforts for an independent air arm achieved results that advanced airpower’s future growth and impact in warfare. The major war which succeeded their time (World War II) proved to be a testing ground for their airpower theories. Several wars after that validated these theories and brought in appropriate modifications in an evolutionary manner. The wars confirmed that airpower proved to be a decisive factor in the war, precision bombing was more effective than area bombing, and civilian morale was more challenging than expected. The prophecy that the bomber would always get through had been overestimated, and the impact of antiaircraft weapons was underestimated. While the WW II experience succeeded in providing the base of tactical air doctrine, subsequent wars shaped the comprehensive airpower doctrines. Airpower is still developing, with newer capabilities and roles being added to it. The original fundamental airpower theories need to evolve with the times.

Suggestions and value additions are most welcome.

For regular updates, please register here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

References:-

- Robert S. Dudney. “Douhet”, Air and Space Forces Magazine, April 2011.

- MAJOR Brian P. O’Neill, “The Four Forces Airpower Theory” A Monograph, United States Army Command and General Staff College

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, May 2011.

- Giulio Douhet, “The Command of the Air”, Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, 2019.

- Carl H. Builder, “The Icarus Syndrome: Air Power Theory and the Evolution of the Air Force” Rand Brief, Oct 1993.

- John F. Jones, “Douhet, Air Power, and Jointness”, Naval War College Review, Vol. 46, No. 4 (AUTUMN 1993).

- Major David Berkland, “Douhet, Trenchard, Mitchell, and the Future of Airpower”, Defense & Security Analysis, Volume 27, Issue 4 (2011).

- Michael D. Pixley, “False Gospel for Airpower Strategy? A Fresh Look at Giulio Douhet’s Command of the Air”, Air University, July 2005.

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.