John Warden. John Warden was born in Texas in 1943. He earned a master’s degree in political science from Texas Tech University, was appointed to the Air Force Academy from Pennsylvania, and graduated in the class of 1965. He conducted a combat tour in OV-10s with the First Air Cavalry Division in Vietnam and a tour in F-4Ds. While at the National War College, Warden wrote a thesis on air operations planning at the theatre level of war. After that, he was assigned as F-15 wing commander at Bitburg, Germany. He remained in that grade when he returned to the Pentagon to head CHECKMATE, an office serving under the Air Force deputy chief of staff for plans and operations concerned with long-range planning. Warden was serving in that capacity at the onset of the Gulf War. After the Gulf War, Colonel Warden was transferred to Maxwell Air Force Base, where he became the Air Command and Staff College (ACSC) commandant. He stirred up that institution greatly, reorienting its study to focus on the operational strategy level of war and air planning at that level. Warden retired from the USAF in 1995. Warden wrote the book “The Air Campaign: Planning for Combat”, which focused on a European war. He seemed to be much more concerned with airpower than with flying aeroplanes.

Core Ideas and Beliefs. John Warden’s core ideas and beliefs, the bedrock of his airpower strategy, continue to reverberate in the field of airpower strategy. His belief in the vital role of air campaign planning, once air superiority is assured, has shaped the way airpower is used in support of other arms or independently to achieve decisive effects. His profound assumptions and beliefs, encapsulated in the following statements, have left an indelible mark on the discourse in the field of airpower strategy:-

-

- Human behaviour is complex and unpredictable, whereas material effects of military action are more predictable.

-

- Victory is and always has been achieved in the mind of the enemy commander—everything must be directed toward that end.

-

- John Warden’s belief in the potency of the offensive in air war is a testament to his strategic mindset. He firmly believed that the offensive is the more potent form of air war, a belief that continues to resonate in airpower strategy.

Theories & Views

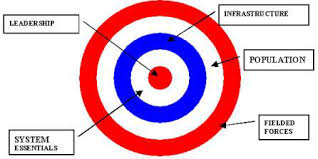

Five Ring Theory. According to Warden, the centres of gravity are arranged in five rings. At the centre are leadership targets, followed by means of production, infrastructure, population, and field forces in the outer perimeter. Fewer centers of gravity (COG) exist in the middle than on the periphery, but they tend to be much more decisive than those on the outer rings. In general, it is preferable to attack the rings from the centre and then move outwards. However, attacking COG in the outer rings can yield a more immediate impact than an attack on the ones at the centre. He advocated that targeting the objectives in all the rings in parallel, rather than sequentially, tends to be even more decisive than attacking only one ring or starting with the outer ring and proceeding inward through each ring in turn.

Targeting. According to Warden, the enemy’s capability should be prioritised because human behaviour and material damage are unpredictable. Warden believed that targeting the enemy’s physical capability (as opposed to his psychological objectives) should be done considering that the military objectives must serve the political objectives.

Joint Operations. Warden’s views on joint operations, an essential aspect of his airpower strategy, instil confidence. He suggests that jointness does not necessarily mean equal portions of the action for all services. He asserts that sometimes airpower should be applied to support the land and sea forces, sometimes it should be supported by them, and sometimes it can be decisive if used independently. He explicitly asserts that single-service operations have been and will continue to be practical sometimes. To him, the other armed forces can function in either a supporting or a supported role, depending on the circumstances. Warden sees occasions when they conceivably will be irrelevant because airpower alone can win some campaigns, a testament to the practicality and effectiveness of his strategy.

Air Superiority. As with the other air power theorists, command of the air remains the Warden’s priority for all operations in the air or on the surface, though it sometimes may be achieved in parallel attacks rather than sequential. In his book “The Air Campaign”, Warden admits that sometimes only a local or temporary air superiority may be possible—and sufficient. Like Douhet, Warden believed the least efficient place for achieving air dominance was in the air. Sometimes, an air attack can serve more than one role. For example, destroying finished petroleum supplies can advance an air superiority campaign as it aids the interdiction effort.

Air Campaigns. Colonel Warden repeatedly suggests that simultaneous operations against all the varieties of target sets can offer significant benefits. The warden’s preference for the offensive largely depends on denying the enemy the ability to react. That denial depends on the size and character of the force and the ability to do so early in the campaign. Like most preceding airmen, John Warden argues that air interdiction by any other name is still preferable to close air support because it allows more targets to be killed at less cost.

Force Structure. Warden adheres to the traditional ideal that airpower should be organised under the centralised command of an airman. The airman should report only to the CINC.

Technology. Warden shows a particular fondness for high-tech solutions. Fundamental to his appeal for the parallel attack is the assumption that the coming of precision-guided munitions (PGM) and stealth make possible the fulfilment of many of the older theorists’ claims that the destruction of a given target required a far smaller strike force than previously, and with stealth no supporting aircraft is needed. At least for now, the stealth bombers can get through with acceptable losses. Now bombers with PGM can get results as fast as Douhet had dreamed. A target can be removed with far fewer bombs than in earlier eras. PGM makes strategic attacks all the more feasible and even makes parallel attacks possible. It grants a modification of the principle of mass, for it allows sending far fewer attackers to a given target and permits the attack of many more targets.

Relevant Excerpts from his book “The Air Campaign”

Levels of War. War is the most complex human endeavour. It is baffling and intriguing. It is also demanding and requires careful thought and excellent execution. The commander’s compelling task is to translate national war objectives into tactical plans at the operational level. The four levels of war are grand, strategic, operational, and tactical. The ambiguity increases as you go up the ladder. Mastery of the operational level strategy is a key to winning wars. It is an art to identify the enemy’s Centre of Gravity (COG – a point where the enemy is vulnerable and where the application of force is most decisive). An air force inferior in numbers must fight better and smarter.

Offensive / Defensive Approach. An offensive approach has many advantages. It retains the initiative while putting pressure on the enemy by taking the war in the enemy’s territory. In this approach, all the assets are used, yielding positive results if successful. On the other hand, in the defensive approach, the initiative is with the enemy, some of the assets may lie idle and at best, it yields neutral results. Adopting the approach depends upon factors like political will, objectives, doctrinal guidance, own vis-à-vis enemy capability, and the force disparity (numerical and qualitative superiority are significant factors). Enemy SWOT analysis and intelligence analysis are essential to deciding on the approach (Consider factors like Aircraft numbers and quality, weapons, training, network, combat support platforms, sensors, ability to absorb losses, vulnerabilities, etc.). A periodic review is required to decide on continuing the adopted approach.

Air Superiority. Air superiority is necessary because air and ground campaigns cannot succeed unless a certain degree of air superiority is achieved. One way to achieve it is by destroying enemy aircraft. Destroying enemy aircraft in the air is the most complex and costly approach (it is easier to destroy them on the ground). However, destroying the enemy aircraft is not the only way to achieve it; it can also be achieved by attacking the enemy bases, fuel and human resources (crew and pilots), production houses and supply chains, and enemy command and control centres. Repeated heavyweight attacks are required to achieve it.

Interdiction / Battlefield Strikes. Interdiction is as old and essential as war—airpower has added a new dimension. It is a powerful, essential, and effective tool for commanders and planners. Airpower should not be seen as airborne artillery. It should generally be used for targets beyond the range of ground weapons. Art is to decide what to and where to interdict between the source and the destination. Distant Interdiction is most decisive but effective with a time lag, intermediate Interdiction is effective with a lesser time lag, and close Interdiction is effective immediately and generally necessary during crises.

Relevant Air Power Application and Air Campaign Planning Principles.

-

- Anticipate and predict enemy reactions and plans. Study and categorise the enemy psyche (rational, irrational, fanatic, rigid, flexible, independent, innovative, and determined).

-

- Audacity does not always lead to positive results—avoid the tendency to plunge into any and every fray. If enemy AD is strong – avoid it till you can punch holes in it and create blind zones. If air combat capability is better than draw the enemy out.

-

- It is difficult to predict the duration and intensity of war. The intensity of war generally depends on the value and interest of the side in what they are fighting for. War effort comes in surges and spurts. Accordingly, the approach could be to continuously engage in a war of attrition or to hit unexpectedly and wait.

-

- Air assets are always scarce—it is not possible to defend everything. Scarce air resources are optimally utilised when shared and not kept idle on the ground—the under-command tendency should be avoided. Scarce air resources cannot be everywhere or precede every surface operation.

-

- An asset not used is an asset wasted – a sortie not flown is a sortie wasted. At the same time, a sortie saved is worth more than a sortie rashly flown. The loss ratio is a function of the force ratio.

-

- Air operations are conducted over larger spaces and at a faster pace than surface operations. Air power should not be considered subordinate (supporting arm) to surface operations. The air element of surface forces should be used according to the tenets of surface operations. Unambiguous and thorough doctrinal understanding is essential.

-

- Operational commanders should avoid tactical decisions – have faith in executors, and concentrate on operational orchestration.

-

- Concentration of forces, mass, numbers, weight of attack and force structure are essential for inflicting prohibitive damage to the enemy. The choice of platform depends on the degree of air control and enemy air defence capability and weapons. In contested airspace, fixed-wing combat support aircraft, helicopters, and unmanned platforms (Drones) are highly vulnerable.

-

- Airpower can carry out parallel operations (campaigns). The percentage of effort allotted to each campaign must be decided and dynamically reviewed periodically, depending on the changing situation.

-

- Bad weather can be a spoilsport—choose the campaign/operational window carefully (the same is true for the enemy). Fog of war, uncertainty in war and friction of war are realities to be dealt with.

-

- Deception (mystify and mislead) is very important to achieve surprise.

In conclusion, Warden’s air power theories represent a transformative approach to military strategy, emphasising the strategic use of air power to achieve decisive and rapid results. Warden’s theories underscore the importance of targeting the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity. His conceptual framework, most notably articulated through the Five Rings model, identifies critical enemy systems—leadership, organic essentials, infrastructure, population, and fielded military forces—as critical targets to disrupt the enemy’s capacity to wage war effectively. Warden’s emphasis on strategic targeting has influenced contemporary military doctrines and operational planning, as seen in conflicts such as the Gulf War and subsequent operations where air power played a pivotal role. Overall, Warden’s air power theories provide a robust framework for understanding and applying air power in modern military operations, highlighting the strategic, operational, and tactical dimensions of employing air forces effectively to achieve national security objectives. The principles he advocated continue to shape the evolution of air strategy, underscoring the evolving nature of warfare in the 21st century.

Link to the Article:-

Suggestions and value additions are most welcome.

For regular updates, please register here:-

References and credits

To all the online sites and channels.

Pics: Courtesy Internet.

References:-

- MAJOR Brian P. O’Neill, “The Four Forces Airpower Theory” A Monograph, United States Army Command and General Staff College

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, May 2011.

- David R. Mets, “The Air Campaign John Warden and the Classical Airpower Theorists”, Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, April 1999.

- David S. Fadok, “John Boyd and John Warden Air Power’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis”, USAF School of Advanced Airpower Studies Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, February 1995.

- Warden, John A III, “The Enemy as a System”, Airpower Journal 9, no. 1 (Spring 1995), 40–55.

Disclaimer:

Information and data included in the blog are for educational & non-commercial purposes only and have been carefully adapted, excerpted, or edited from reliable and accurate sources. All copyrighted material belongs to respective owners and is provided only for wider dissemination.